by Geoff Olson

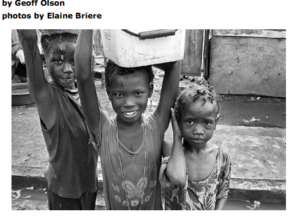

photos by Elaine Briere

David Putt, a retired agrologist/geologist from Nelson, BC, stands before a display of artwork from Port-au-Prince. The semi-abstract masks, hammered from oil drums, seem to radiate a comic, defiant spirit. “Arts are alive and well everywhere, and they’re a part of people’s daily lives,” says the grey-haired, soft-spoken Putt, pointing to the pieces he and his partner, photojournalist and filmmaker Elaine Brière, brought back from Haiti. The masks add a Caribbean touch to the living room of Brière’s East Vancouver home, which is decorated with photographic prints from around the world. Putt attests to the incredible spirit of the Haitian people, in spite of what they went through. “It was one of the most remarkable things to me,” he notes.

Putt, who came to Haiti to work with the NGO Pure Water for the World, was in the basement of an office building in Port-au-Prince when the earthquake hit on January 12. Terrified, he and two co-workers dove under a rickety table. Although the building was damaged beyond repair, it did not collapse. Everyone inside survived, and after a seeming eternity of quaking, they gathered outdoors, shocked and shaking. Putt looked to the horizon, at a cloud of dust so thick it completely obscured a nearby valley where many dwellings had come down. He could see the hill above, in the greener, leafier neighbourhood where the wealthy lived. “Every few moments a wall or a house up there collapsed,” he remembers. “Maybe 20 minutes after the quake, we saw a large building crumble and slide down the hill, those trapped inside screaming as it went.”

After retrieving water from the building, Putt and a co-worker set out for home in the gathering darkness. “At first it was eerily quiet except for a few on the street crying, a few others moaning in the wreckage. Even the children were quiet. Bodies and some of the badly injured were already being laid out on the street – one had to be careful not to step on them in the dark. Groups had gathered and some began singing, hymns mostly, often in a beautiful, otherworldly chant and response that I found chilling and comforting at the same time.”

As other observers noted at the time shortly after the quake, some Haitians consoled themselves by singing through the nights.

Immediately following the 7.0 earthquake, which devastated the capital city of Haiti, the global media networks went into high gear. For two weeks – a lifetime in the 24-hour news cycle – viewers were bombarded with footage and reports of Haitians mourning their dead and rescuing the lucky few who survived the wreckage. The quake ultimately claimed 230,000 lives, injured 300,000, and rendered 1,000,000 homeless.

In the brief period in which global attention was fixed on Haiti, international relief programs segued into Live-Aid style philanthropy. At a certain point, it seemed this carnival of altruism became less and less about Haiti and more about us – best evidenced by the self-congratulation of performers and pundits in the developed world, singing these poor black people back to civilization, and away from mother nature’s random acts of unkindness.

This isn’t to diminish the very real concern of people around the world, who extended a helping hand to the Haitians. It’s not as if the aid was unnecessary or unappreciated. It’s just that the Bono-Rhiannon showmanship melded smoothly with Bush-Clinton statesmanship. The telegenic charity further concealed, rather than revealed, the Caribbean heart of darkness midwived by western powers long before the quake.

Haiti is frequently described as the poorest country in the western hemisphere, notes Canadian political philosopher Peter Hallward, author of Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide, and the Politics of Containment. “This poverty is the direct legacy of perhaps the most brutal system of colonial exploitation in history, compounded by decades of systematic postcolonial oppression,” he notes in a January 2010 article in The Guardian.

Haiti takes its name from the language of the Taíno, the indigenous people who were wiped out through a combination of European-imported disease and the killing sprees of Christopher Columbus’ soldiers.

The Republic of Haiti became the first independent country in Latin America, in 1804 – a black-led republic conceived in the world’s only successful slave revolt. At the time, the colonial powers were all slave-owning societies and they did not recognize the republic for decades. And although slave-owner Thomas Jefferson supported the emigration of American slaves to Haiti, he also felt a republic of emancipated negroes might send the wrong message to the toiling, sweating property of American plantation owners.

Even before the earthquake reduced Port-au-Prince to stone-age conditions, the average life expectancy in Haiti was 57 years, with the lowest caloric intake per person in the western hemisphere. While I admired the collection of Haitian art, Elaine Brière handed me a book of photos, open to a picture of a young girl making what appear to be mud pies. “These are not ordinary pies,” the text reads. In Port-au-Prince, women and girls fashion them and sell them in the streets. They are made from salt, water, flour and mostly dirt. The patties are dried in the sun and sold at markets to the poorest of the poor who are fully aware of the ingredients. “When asked why the poor would knowingly eat the dirt pies, a girl responded in the most matter of fact way, ‘So they won’t die hungry.’”

Brière saw such mud pies for sale in the streets of Haiti, just weeks before “Le Tromble,” as the earthquake was known in Creole. She left just days before the quake, while her partner David Putt stayed to assist with the aid efforts.

Eight days after the quake, Putt emailed Brière, noting his efforts in delivering aid were becoming more desperate. The US military had claimed the airport and he couldn’t understand the holdup. “There was a huge amount of traffic on the road but most was not aid related,” he wrote. In the chaos of central Port-au-Prince, there was little evidence of relief. “All day long, heavy helicopters whack, whack, whack across the skies above Champs de Mars (the Parliament Hill of Haiti) – I counted 22 in two hours on Sunday. They never land. I have met no one, local or aid worker, who knows where they are going.”

It was day eight since the quake. Where were the food and the medical supplies? Putt wondered. “Canadians have rioted in Vancouver and Montreal over things as simple as the Stanley Cup. People have been stoically holding on here under conditions unimaginable,” the retired geologist wrote. On the second Saturday after the earthquake, he got word that medical supplies were piling up at the Canadian base and the military would have to stop bringing in more unless some were picked up.

He turned up the next day with an empty truck, with all his necessary documentation, including ID showing that he was with an NGO. But all he could get from the Canadian military were phone numbers of CIDA (Canadian International Development Agency) back in Ottawa – an absurd response, given the problem finding any working phone lines. He left with nothing. At the gate, he watched as a youth group running a clinic was turned away, even though they were led by a doctor making an emergency request for medicine, with all his credentials in order.

Putt puts the SNAFUs he saw down to a lack of coordination between the big NGOs and all the different military units. In an April 23 article posted at the Common Dreams website, aid worker and Seattle school teacher Jesse Hagopian echoed Putt’s observations, having witnessed similar misadventures in relief response from the US side.

“Regrettably, the most prevalent explanation in the media for the sluggish delivery of aid was that authorities anticipated rioting by the violence-prone Haitian people. This well-worn, racist narrative attempted to transform Haitians from victims of an earthquake to perpetrators of a security threat. However, my wife and I didn’t see a single instance of rioting or violence in the week we were there,” Hagopian writes.

Early on, the US could have exercised the option to use C130 transports to drop supplies in Port-au-Prince, but Secretary of Defense Robert Gates rejected this option, insisting that “air drops will simply lead to riots.” Putt sees this attitude in the context of the Americans’ terror-alert culture of fear, although their institutionalized paranoia is not completely disconnected from reality, in the case of Haiti.

According to Putt, “The US military has a long history of crushing resistance to oppression in Haiti – a lot of Haitians dislike them intensely and the upper echelons of the military and their civilian minders must know it. Given that context, I am not surprised that they were excessively preoccupied with security when they arrived in Haiti and when they finally ventured out it was in ridiculously over-armed convoys. That did eventually change with time after the quake.”

The UN has its own – and very recent – history of violent repression in Haiti, notes Putt. “They’re seen as an occupying force by most Haitians. When they dare to enter Cité Soleil [the largest, poorest slum in Port-au-Prince] it’s always with guns cocked and waving at the ready. So again, it doesn’t surprise me that their large military contingents, the agents of the repression, were also preoccupied with security in the immediate aftermath of the quake. To me, both the US and UN approach was in good part a response to the enmity they had brought on before.

“US Repression of Haiti Continues” is among Project Censored’s top 25 censored news stories for 2009. Prior to the earthquake, the US government planned to expropriate and demolish the homes of hundreds of Haitians in the shantytown of Cité Soleil, the epicentre of organization for the Fanmi Lavalas party, to expand the occupying UN force’s military base. The base is intended to house the soldiers of the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH).

“Cité Soleil is the most bullet-ridden battleground of the foreign military occupation, which began after US Special Forces kidnapped and exiled President Jean-Bertrand Aristide on February 29, 2004. Citizens have since been victimized by recurring massacres at the hands of MINUSTAH,” according to Project Censored.

Haiti’s 200-year history does not paint a picture of good intentions from foreign powers. Back in the mid-1700s, France derived half its gross national product from its colony in the Caribbean, “the jewel of the Antilles.” True independence was never part of the colonial or postcolonial script. In July 1825, King Charles X of France dispatched a fleet of 14 vessels with thousands of troops to reconquer the island. As a result, the embattled first President of Haiti, Jean Pierre Boyer, agreed to a treaty in which France formally recognized the independence of the nation in exchange of reparations. The price, 150 million francs, was estimated for profits lost from the slave trade.

In 1838, France reduced the price to 90 million francs, which, by 1947, was paid by Haiti in full, and with interest many times over. During his tenure, Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide travelled to France to petition for the return of the reparations, but was rebuffed by the French government.

Aristide, a former priest with a hankering for liberation theology (a form of Christian social activism inspired by Christ’s compassion for the poor) won two thirds of the popular vote in the 1990 general election. He was displaced in a 1991 military coup and was returned to power by the Clinton administration in 1994, under the condition he not steer the nation away from US-engineered free trade policies, which turned out to conflict with his desire to lift his people “from absolute misery to a dignified poverty.” The former priest vacated the presidency in February 1996, the scheduled end of his five-year term, but was re-elected by massive popular support in 2000. In 2004, Aristide was overthrown a second time, in a foreign military intervention that involved Canada, the US and France and received authorization from the United Nations Security Council.

Reports about Aristide are confusing and contradictory. Some US media outlets have painted him as a thief and drug-runner, who stole millions of dollars from the country and used paramilitary forces to threaten opponents. The Wikipedia entry on Haiti cites a number of sourced accusations against the former priest, but adds, “the accuracy of the information is questionable and may have been concocted to discredit Aristide.” Certainly, the former priest was no worse than the violent despots that have ruled Haiti, since its inception, with the tacit or active approval of foreign powers. From 1957 to 1986, the family dynasty of Baby Doc Duvalier ruled with an iron fist, turning the island into a torture chamber through the dreaded Tonton Macoute police force.

In a March 9 interview in Counterpunch, MIT media critic Noam Chomsky claims the US and France, “the two traditional torturers of Haiti,” kidnapped Aristide in 2004, “after having blocked any international aid to the country under very dubious pretexts, not credible grounds, which of course extremely harmed this fragile economy. There was chaos and the US and France and Canada flew in, kidnapped Aristide – they said they rescued him, they actually kidnapped him – they flew him off to Central Africa, his party Fanmi Lavalas is banned, which probably accounts for the very low turnout in the recent elections, and the United States has been trying to keep Aristide not only from Haiti, but from the entire hemisphere.”

Whatever Artistide’s merits were as a leader, the party that elected him into power, Fanmi Lavalas, is now barred from participating in general elections. That’s a fact worth remembering whenever foreign dignitaries and diplomats trot out their boilerplate pieties about advancing democracy in Haiti.

Chomsky adds there has been a very explicit program by US AID and the World Bank to destroy Haitian agriculture and speed the flight of rural villagers to the urban centre, where sweatshops absorb the influx of desperate labourers. “They gave an argument that Haiti shouldn’t have an agricultural system, it should have assembly plants; women working to stitch baseballs in miserable conditions. Well, that was another blow to Haitian agriculture, but nevertheless even under Reagan, Haiti was producing most of its own rice when Clinton came along.”

In the Clinton years, things got even worse for Haitians. During the ‘92 US presidential election campaign, the former governor of Arkansas promised to help the country and allow fleeing Haitians to take refuge in the United States. Yet after the election, Slick Willy began to interdict refugee ships and return the scared and starving passengers back to their homeland.

The latest occupant in the Oval Office has given no sign that hope and change are long-term goals for Haiti, certainly not after he appointed Bill Clinton to oversee US relief efforts in Haiti, along with George W. Bush, who presided over the federal non-response to homeless blacks after Hurricane Katrina.

In the past, gunboat diplomacy has kept Haitian experiments in self-autonomy in check. Today, barbarians with briefcases accomplish this goal through firm handshakes and spring-loaded agreements. The infamously punitive neoliberal reforms of the so-called “Washington Consensus” force the country to lower its protective tariffs, eliminate social services and incur even greater debt through bank loans. The lower tariffs allow Haiti’s food markets to be swamped by staples from heavily subsidized US agribusiness and the increased austerity means even greater privation for the population, more than half of which struggles along on less a dollar a day.

The IMF and World Bank cancelled $1.2 billion of Haiti’s debt last year, and in January, the World Bank waived Haiti’s $38 million debt payment for five years, while offering a $100 million loan, interest free until the end of 2011. As it rebuilds from the earthquake, Haiti will still be a debtor nation. The IMF and World Bank – ‘Thing One and Thing Two’ in this tale of Fat-Cat-in-a-Hat capitalism – are not about to give up on Haiti.

And now, months after the earthquake, things are returning to the Haitian level of normalcy, which means the usual political instability. In mid-April, The Observer reported that angry Haitians are arming themselves against the government, after watching most of the quake relief benefit the wealthy elite. Certain politically unpalatable areas that needed relief the most, like Cité Soleil, were studiously avoided by most NGOs in the critical days after the quake, claims David Putt.

Along with the US and France, Canada has played a significant role in political interference in Haiti, including the nabbing of Aristide. Recovering from what he experienced during his post-quake relief adventures, Putt says he’s having difficulty managing his anger – that is, anger at Canada’s political culture of wilful blindness, where few of us venture outside our safety zones, whether mental or geographic. He notes the irony that, after the volcanic eruption in Iceland, local newscasters broadcast scene after scene of air travellers stranded at airports, some sleeping with heads on their luggage, as if something terrible had happened to holidaying Canadians. Yet far below the contrails painted across blue Pacific skies by charter flights, some of the descendents of history’s only successful slave revolt are literally reduced to eating dirt.

“I was surprised by how proud people in Haiti are,” says Putt. “There is a real pride in their history, in knowing that they had a successful revolution, and there’s a pride in having resisted ever since. Everybody had a go at them, the Germans, Spaniards, French, British and Americans.”

In spite of their suffering – or perhaps because of it – some Haitian street artists are still capable of producing the kind of artwork that would find pride of place in most year-end art-college shows. Looking at the charming symmetry and sly humour of Putt’s collection of Haitian masks, I think of a line from the 13th century Persian poet, Rumi: “Gold becomes more and more beautiful from the blows the jeweler inflicts on it.”

“I was astounded at what a rich culture it is,” Putt says with a mix of admiration and sadness, gazing at the masks on the wall. “Its absolutely unique. There is vitality to the culture. In parts of Latin America, especially the poorer people, there is a beaten down feel about the society. Whereas Haitians, against all reason, seem to hang on to hope.”

Hey, is there a section just for newest news

Yes, there is- That would be the HOME PAGE http://www.haitian-truth.org

Enjoy reading.

Also, click the dates on the calender to see the postings from that date