The following is not easy reading, but I am trying to balance an honest and unvarnished assessment of the current crisis in Haiti with specific suggestions to immediately address the situation.

While the popular uprisings now sweeping through Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador are national in scope, the uprising in Haiti is quickly becoming a full scale international humanitarian crisis as the country runs out of food and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, are suffering severe hunger and don’t know when they will eat again. The UN’s World Food Program has warned that one third of the 11 million people in Haiti are in need of immediate food assistance, with 1 million of those now “on the brink of famine.”

|

|

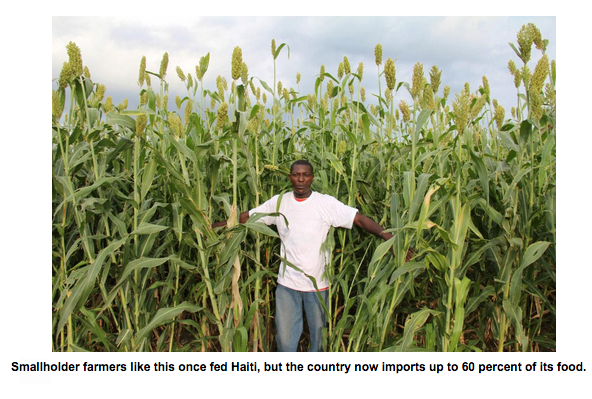

Smallholder farmers like this once fed Haiti, but the country now imports up to 60 percent of its food.

|

A groundswell of public anger at conditions in Haiti led to sporadic protests that began over a year ago. Initially the anger was fueled by outrage over disclosures detailing government corruption. Then came fuel shortages, rampant inflation and food being both expensive and in short supply. These issues coalesced in a new round of much larger and more sustained protests and street demonstrations that began in September, all demanding the removal of President Jovenel Moïse.

At first these were raucous but mostly peaceful expressions of the public mood, eventually gaining sufficient momentum to result in a national lockdown known locally as peyi lòk. But the protests were gradually hijacked by armed gangs sponsored by various players in the current national drama. The police force does not have the numbers or capacity to contain the gangs and so they essentially operate without restrictions. Haiti’s national lockdown is now an armed conflict that has essentially brought life to a halt and the economy to a standstill. And just as the lockdown and related protests are beginning to lose momentum in recent days and give a glimmer of hope, the country is now faced with the specter of famine.

How did this food crisis happen and what can be done to help the country recover?

The response represents two sides of a coin called agriculture. And more specifically, agriculture as practiced on the approximately 500,000 smallholder farms of 2 hectares (or 5 acres) or less that constitute the backbone of the country’s rural economy, albeit an underperforming economy.

Haiti now imports up to 60 percent of it food, including 85 percent of the rice that is the country’s most important staple. But as recently as the late 1980s, Haiti’s farmers grew almost all the country’s food. At that time agriculture accounted for about 35 percent of GDP, 24 percent of all exports, and 66 percent of the labor force. While acknowledging that the country then was desperately in need of institutional and human rights reform, Haiti was nonetheless a self-sufficient agricultural economy.

What changed? It boils down to the systematic removal of all forms of support for the smallholder farmers of Haiti. This is not about handouts. It is about the removal of agricultural training, financial services, protective tariffs, crop research, livestock breeding, government supported irrigation (some still exists, but much is in disrepair and it has not been expanded for decades), and reliable and affordable sources of seed and supplies.

When a small country like Haiti is dependent on imports, it becomes vulnerable. Any combination of inflation, fuel shortages or disruption of ports can have serious consequences. We now have all three in play at once, along with climate-related lower than average yields from already under-producing farms, leading to food shortages. Add to this a national lockdown reinforced by armed gangs and you have famine.

So back to the question of what can be done to help: I would suggest three categories of assistance.

First is sending food aid from outside the country, which will also involve the World Food Program releasing the reserves it currently has on hand in Haiti for this purpose (and which they have already begun to do). But there is nowhere near enough food in those reserves to respond to the scale of the crisis. The related challenge will be moving this food aid around the country with armed gangs in control of the major highways. And all this is within the purview of governments and international institutions.

The second thing I would suggest, and which may seem out of sync with the gravity of the crisis, involves assisting by changing the narrative regarding Haiti. To all journalists I make this request: stop referring to Haiti as “the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.” To the public I make this request: if you see this in print or online, send a response to the author or website asking them to refrain from using this hackneyed trope. While the phrase may be technically accurate, it relegates an entire country and its people to a write-off category. All Haitians are full status members of the human family without condition. This is a culturally rich country with a unique history and they are following their own sometimes challenging path as an emerging democracy. Haitians are worthy of the kind of compassion and support that is not tainted by being relegated by this offensive phrase to a sub-category not fully worthy of inclusion in the global community of nations.

The third action I would like to suggest is a long-term, concerted and coordinated effort by a coalition of NGOs, businesses and the Government of Haiti to revive smallholder agriculture throughout the country and make it productive once again. While a purely Haitian government-led solution is a best-case scenario, that has not happened over the past 30 years and is unlikely to spontaneously manifest in the near future.

The Government, as it stands now, simply does not have the capacity to do this on its own. It will soon have even less capacity because of elections having been postponed. Come January, there will technically be 11 elected members left out of 149. There will be no members left in the 118-seat Chamber of Deputies, and only 10 out of 30 members of the Senate (which is not a quorum). Those 10 senators will be joined by the President as the only elected officials left in office representing both the parliamentary and executive branches of government.

As of now there is no duly constituted Prime Minister or cabinet because those currently holding these interim positions have not been ratified by the current government, and come January there will be no new government with the authority to make that determination. The current deputies and senators about to leave office may well decide to extend their mandate, but they will, by definition, be operating in an interim capacity. This will leave the President to govern by decree in the absence of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate that are functioning as defined by the constitution.

Without waiting for the government to get back to a full working state (which could take a while), there are highly capable technicians from the Ministry of Agriculture who are ready to work on developing a new smallholder-centric agricultural strategy in concert with some of the Haitian and international NGOs that now work in the agricultural sector, as well as several agricultural businesses.

Given the opportunity, such a coalition could put together a strategy to be implemented on a community-by-community basis in the short term. Long term leadership of the operation would revert to the Ministry of Agriculture once they are able to take on that role, and a key part of the strategy from the outset would need to be strengthening the capacity of the Ministry itself.

In our small corner of the agricultural world in Haiti, those participating in the Smallholder Farmers Alliance generally see yield increases of at least 40 percent once they have earned high quality seed, good hand tools and basic agricultural training by planting trees. So we know that smallholders have the capacity to feed their country. We are just one group among many that have proven models ready to be replicated and adapted to work in concert with others.

Restoring the agricultural prosperity of Haiti is not rocket science, but neither is it business as usual. It will take nothing short of a full-scale agricultural revolution to set things right again. Surely enough citizens have now paid the price for food insecurity. It is up to the rest of us to act now and without delay.

Regards,

|

|

Hugh Locke