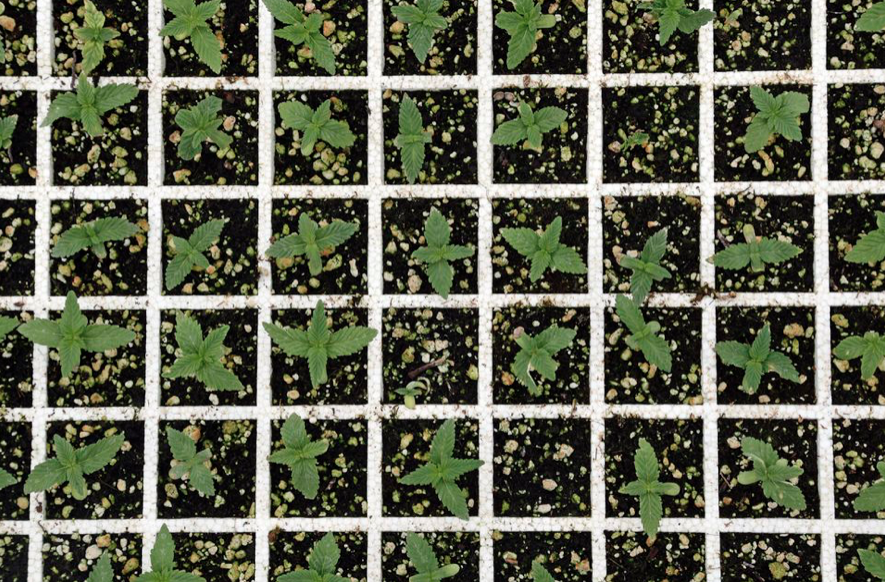

The hemp fields sprouting in a part of Canada best known for its giant oil patch show how climate change is disrupting the construction industry.

Six years after setting up shop in the shadow of Calgary’s tar sands, Mac Radford, 64, says he can’t satisfy all the orders from builders for Earth-friendly materials that help them limit their carbon footprints. His company, JustBioFiber Structural Solutions, is on the vanguard of businesses using hemp — the cousin of marijuana devoid of psychoactive content — to mitigate the greenhouse gases behind global warming.

Around the world, builders are putting modern twists into ancient construction methods that employ the hearty hemp weed. Roman engineers used the plant’s sinewy fibers in the mortar they mixed to hold up bridges. More recently, former White House adviser Steve Bannon weighed in on using so-called hempcrete to build walls. Early results indicate it’s possible to tap demand for cleaner alternatives to cement.

“We have way more demand than we can supply,” said Radford from his plant in Airdrie, which is undergoing expansion and soon expects to churn out enough Lego-like hemp bricks each year to build 2,000 homes.

Greener alternatives to cement add to the pressure on companies including LafargeHolcim Ltd. and Votorantim Cimentos SA as the global economy pivots toward dramatically lower emissions.

Cement makers are responsible for about 7 percent of global carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere every year, with copious volumes entering via limestone kilns needed to produce the material. Manufacturers say they’ve struggled to find markets for greener alternatives, giving easy entree to entrepreneurs like Radford who cater to customers concerned about their impact on the Earth.

“They love it once they understand it,” said Radford of the builders who’ve adopted the modular, inter-locking bricks he invented for their projects. “Our old practices we have to change.”

While architects and developers have traditionally concentrated on the energy used by their buildings once they’re standing, it’s actually the materials required in their construction that represent the brunt of a structure’s lifetime carbon footprint. Replacing high-carbon-intensity materials like cement with greener alternatives like hemp can dramatically reduce or even offset greenhouse gas pollution.

Hemp fields absorb carbon when they’re growing. After harvest, the crop continues to absorb greenhouse gases as it’s mixed with lime or clay. Hempcrete structures also have better ventilation, fire resistance and temperature regulation, according to their proponents.

Numbers across the industry vary depending on the process, but JustBioFiber says that its hemp captures 130 kilograms (287 pounds) of carbon dioxide for each cubic meter it builds. Those structures made with their bricks will sequester more greenhouse gases than they emit in production. By contrast each ton of cement produced emits half a ton of carbon dioxide, according to the European Cement Association.

First developed in France more than 30 years ago, hempcrete was initially used for renovating old houses because it mixed well with stone and lime. That has progressed to build new homes, offices, and municipal buildings, some as tall as seven floors, according to Quentin Pichon, founder of CAN-Ingenieurs Architectes who specialize in hempcrete buildings.

Hemp growth in France has grown by fifth in the last decade as a result of an increase in its construction use but also because seeds from the plant that can be used to make cannabidol, he said. Hemp sales in Canada could hit $1 billion within five years from $140 million last year, according to the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology.

That ability to quickly ramp-up local cultivation virtually anywhere in the world is one of hemp’s appeals, according to Alex Sparrow, the managing director of UK Hempcrete.

“Demand is rising steadily but we need to accelerate this as currently the UK construction industry accounts for approximately 7 percent of GDP and 50 percent of total UK carbon emissions,” Sparrow said.

One of the principle challenges his UK company faces are legal hurdles imposed on hemp cultivation. British farmers can only grow hemp building materials but can’t profit from the oil extracted from seeds.

Back near Calgary, the black denim-clad Radford is already turning a profit from his hemp venture and is preparing to invest another $37 million Canadian ($28 million) to expand production to 3.5 million bricks a year. He credits his children with convincing him to go green after four decades in commercial development.

“They think that finally it’s not about money, it’s about doing good for the planet,” he said.