BBC.com

Venezuela’s president has said its subsidised fuel prices should rise, to stop smugglers cheating the country out of billions of dollars.

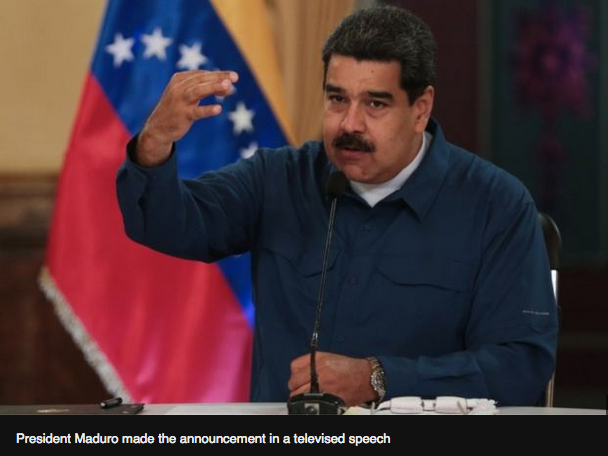

“Gasoline must be sold at an international price to stop smuggling to Colombia and the Caribbean,” Nicolás Maduro said in a televised address.

Like many oil producing nations, Venezuela offers its citizens heavily subsidised petrol.

A fuel price rise in 1989 caused deadly riots in the capital, Caracas.

What’s behind the move?

Venezuela’s economy is in freefall, with the International Monetary Fund predicting inflation rates will reach a million percent this year – but the price of fuel has barely changed.

- Venezuela crisis: How did we get here?

- Venezuela deploys soldiers to markets

- Profile: Venezuela’s controversial leader Nicolás Maduro

The price of a litre of petrol in Venezuela currently stands at 1 bolivar. On the black market, Venezuelans pay more than 4m bolivares for one US dollar.

That means that for the equivalent of one dollar, Venezuelans can fill the tank of a medium-sized car about 720 times.

Media captionVenezuelan cash crisis: How a coffee costs wads of banknotes

Smuggling the subsidised fuel from Venezuela into neighbouring countries, where prices are much higher, is big business.

Venezuela loses $18bn to fuel smuggling annually, according to government figures. President Maduro says adapting Venezuelan fuel prices to international levels will stamp out smuggling.

The move is part of a wider plan to increase government revenue in the face of falling oil production, Venezuela’s main export income.

Will all Venezuelans have to pay full whack now?

No, according to President Maduro “only those individuals who don’t answer the call to register will have to pay fuel at international prices”.

The president said that all Venezuelans who hold the “Fatherland ID”, a government-issued identity card introduced by his administration in 2017, will continue to receive “direct subsidies” for “about two years”.

However, many Venezuelans opposed to Mr Maduro’s government have refused to get the ID cards, alleging they are used by officials to keep tabs on them.

The price rise is therefore expected to hit opponents of President Maduro in greater numbers than those who support him.

President Maduro said he would announce further details of how the new subsidies scheme would work in the coming days. It is expected to come into effect on 20 August.

What’s the ‘Fatherland ID’?

President Maduro introduced the new ID card in January 2017 arguing it would serve to make his socialist government’s social programmes more effective.

Image copyrightEPAImage captionCritics of President Maduro refuse to apply for the “Fatherland ID”

Getting the ID is free and voluntary for anyone over 15 but those who apply have to answer a series of questions about their socio-economic status and what state benefits, if any, they are receiving.

According to government figures, by January 2018, 16.5 million Venezuelans out of 31.5 million citizens had applied for a “Fatherland ID”.

Only those who are in possession of the ID can apply to receive subsidised food parcels and other state benefits.

Government critics opposed the introduction of the Fatherland ID from the start, arguing that there was no need for it as Venezuelans already had government-issued ID cards.

They said that it was a way to restrict the hand-out of state benefits to government supporters. They also fear that the government uses the Fatherland ID to collect information on citizens.

Will the new measure end smuggling?

Unlikely, as smugglers who hold a Fatherland ID or apply for one will still be able to buy fuel at rock bottom prices and sell it at a massive profit in Colombia and other countries.

Image copyrightGetty ImagesImage captionVenezuelan subsidised petrol is smuggled across to Colombia in gerry cans

Some opposition politicians fear that the measure will be used as a way to introduce petrol rationing through the back door by limiting the amount each individual can buy on his Fatherland ID. But so far no limits on the amount of petrol people can buy have been announced.

Why are fuel price rises so controversial?

Venezuelans are very car-dependant. It is not unusual for families to have multiple cars and for them to drive long distances to work.

Image copyrightGetty ImagesImage captionIn the city of Maracaibo, military trucks have been used to transport people

For those who cannot afford cars getting around has become increasingly difficult. Public transport is poor and has worsened in recent years as a lack of maintenance has led to a shortage of public buses.

Venezuelans complain about having to queue to get on trucks previously used to transport livestock. Many spend hours commuting to and from work.

A rise in the price of fuel would not just hit those who drive their own cars as companies running bus routes would likely pass on the price hike to their customers.

There have been very few fuel price rises since 1989 when such a rise – amid other austerity measures – sparked massive riots in Caracas and its environs.

Image copyrightGetty ImagesImage captionA rise in the price of petrol, food and public transport led to riots in 1989

The president at the time sent troops into the streets to quell the riots and hundreds of people were killed.

The incident, known as the Caracazo, has haunted Venezuelans ever since.

What’s at the root of Venezuela’s economic crisis?

Venezuela is rich in oil. It has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. But it is arguably precisely this wealth that is also at the root of many of its economic problems.

Venezuela’s oil revenues account for about 95% of its export earnings. This means that when oil prices were high, a lot of money was flowing into the coffers of the Venezuelan government.

When socialist President Hugo Chávez was in power, from February 1999 until his death in March 2013, he used some of that money to finance generous social programmes to reduce inequality and poverty.

But when oil prices dropped sharply in 2014, the government was suddenly faced with a gaping hole in its finances and had to cut back on some of its most popular programmes.