PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (Tribune News Service) — In a country where virtually all the news lately has been bad, Lucmane Tabuto found the announcement that cholera had resurfaced particularly worrisome.

The 65-year-old former carpenter thought back to his own experience with the waterborne disease more than a decade ago. U.N. peacekeepers, deployed to this Caribbean nation after the 2010 earthquake that killed around 220,000 people, improperly disposed of sewage waste and contaminated a river, setting off an outbreak that killed 10,000 people and sickened more than 820,000.

Tabuto thought about how he was hospitalized for weeks and unable to work for a month. How his wife and one of his children almost died of the waterborne disease. How the ordeal devastated his family’s finances. How he’s still dealing with the effects – and still waiting to be made whole.

“They brought cholera to Haiti and they need to compensate us,” Tabuto said. “It’s an injustice. It’s an unspeakable abuse.”

As cholera races across Haiti, propelled in part by an escalating security crisis, the United Nations is mulling a request from Haiti’s government for “a specialized armed force” from abroad to quell the gang violence that has hindered the response and brought the nation of 11 million to the precipice of anarchy.

But the request, which has been backed by U.N. Secretary General António Guterres and the Biden administration, is a divisive and delicate subject here, where the shadow of a long history of destabilizing foreign interventions, including the U.N. mission that introduced cholera, looms large.

And it’s renewing questions about accountability and redress. The United Nations in 2016 pledged $400 million in a “new approach to cholera,” but has raised only 5 percent of the sum, while drawing criticism for failing to center victims in its decisions.

“It’s really terrible,” said Mario Joseph, a Haitian lawyer who has helped lead efforts to seek redress for cholera victims. “They gave us cholera, they didn’t do anything to eradicate the cholera” and they are using its resurgence as a “pretext” to return, Joseph said.

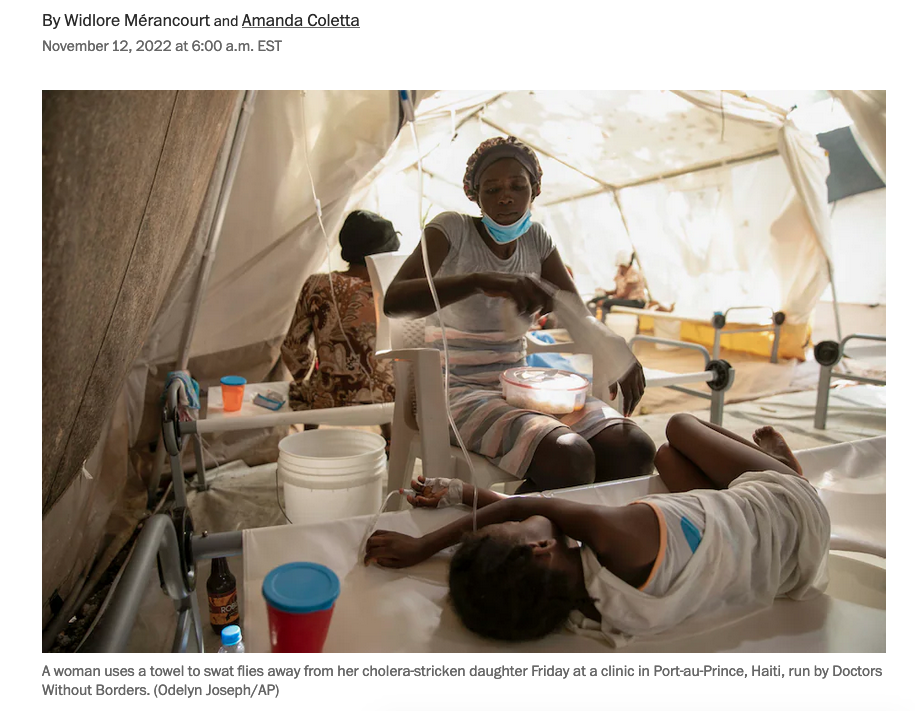

Haiti has suffered more than 6,800 suspected cases and more than 100 deaths since officials reported on Oct. 2 that cholera had resurfaced after three years without a new case. Diagnoses of the disease, which is easily treatable but can cause death within hours if left untreated, have doubled in the last week alone.

“Cholera is gaining ground,” said Jeanty Fils Exalus, a spokesman for Haiti’s health ministry. “We have to mobilize way more resources.”

That’s easier said than done. Gang violence, which has intensified since the brazen assassination last year of President Jovenel Moïse at his home outside the capital, has impeded access to health care, fuel, clean drinking water and other aid. There are effective vaccines for cholera, but the government hasn’t approved a vaccination plan.

Tabuto listens for news about cholera on the radio from his home in Jérémie, a city in southern Haiti. Clean water is scarce. Water purification tablets are in short supply.

“If the cholera comes to Jérémie,” he said, “it will be worse than the outbreak of 2010.”

Cholera was nonexistent here before it was introduced in 2010 by a contingent of U.N. peacekeepers from Nepal, where cholera is endemic. They improperly disposed of latrine sewage in a tributary of the Artibonite River.

For years, the United Nations refused to acknowledge its role in the outbreak, even as scientific evidence piled up, and it sought to skirt legal responsibility by invoking diplomatic immunity. In 2013, it rejected compensation claims.

Hundreds of displaced Haitians live in make-shift homes outside Gheskio Field Hospital, located on Quisqueya University grounds, where International Medical Surgery Response Team technicians are providing emergency medical attention to Haitians following a 7.0 magnitude earthquake near Port-au-Prince on Jan. 12, 2010. (Joshua Kelsey/U.S. Navy)

In 2016, the U.N. special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights condemned the organization.

“The existing approach is morally unconscionable, legally indefensible and politically self-defeating,” Philip Alston wrote. “It is also entirely unnecessary . . . [It] upholds a double standard according to which the United Nations insists that member states respect human rights, while rejecting any such responsibility for itself.”

Later that year, then-secretary general Ban Ki-moon apologized for the organization’s role in the outbreak, saying it blemished “the reputation of U.N. peacekeeping and the organization worldwide.”

He announced a “new approach,” promising $400 million in funding for improved sanitation and water infrastructure and for “material assistance and support” to severely affected victims. Five years later, it has raised only $21.8 million.

“The resurgence of cholera in Haiti today is a direct result of the U.N.’s failure to keep its promises,” said Beatrice Lindstrom, a clinical instructor at Harvard’s International Human Rights Clinic who worked with Joseph to bring class-action lawsuits against the international body.

Victims and their advocates have criticized the United Nations for opting for community-based projects instead of direct compensation to victims who lost wages, saw family finances falter after their breadwinners died and still struggle with illness.

“If this happened in the United States or in Canada or in Australia and the official response was, ‘We’re not giving any compensation to individuals even though there was a direct link between the death of your relative and the actions of the United Nations . . . but we will build a new community home, we might set up a new health center,’ ” said Alston, now a law professor at New York University, “that would be met with outrage.”

Stéphane Dujarric, a spokesman for Guterres, acknowledged that the “new approach” is “underfunded,” in part because contributions are voluntary. He cited this funding gap as one reason the United Nations is moving ahead with community-based projects over direct compensation.

The lessons from 2010 are being used in the current response, which can interrupt chlorea transmission if the effort is fully funded, he said. The international community has spent $705 million fighting cholera in Haiti since 2010, he added.

Dujarric said that some recent donor contributions were allocated to a surveillance mechanism that Haitian authorities used to identify cholera’s resurgence last month. “. . . Ultimately, however, Haiti will continue to suffer from outbreaks of waterborne diseases until the country develops water, sanitation and hygiene systems that are robust, equitable and sustainable,” he said.

The U.N. Security Council voted unanimously last month to impose sanctions on Haitian gang leaders, and the United States and Canada have levied sanctions on the president of Haiti’s senate and his predecessor for their alleged roles in supporting the gangs.

But the panel hasn’t come to a decision on a U.S. resolution that would authorize a “non-U. N. international security assistance mission” to help Haitian police restore order and to enable the movement of humanitarian aid. The United States does not want to lead the force.

Though Haitian police last week regained control of a key fuel terminal that had been blockaded by a gang for nearly two months, State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters this week that this did not diminish the need for a foreign force.

“There is still urgency,” Price said. “The status quo remains untenable.”

U.S. officials have pressed Canada to lead the force. Canada dispatched a team to Haiti last month to assess needs. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said there must be intervention “in one way or another,” but has not specified what it might entail.

When Wien-Weibert Arthus, Haiti’s ambassador to Canada, appeared before a parliamentary committee in Ottawa this month, several Canadian lawmakers voiced unease about deepening the country’s involvement in a country where a political consensus remains elusive and the interim prime minister lacks popular legitimacy.

The main difficulty a foreign security force would face on the ground, Arthus said, was “acceptance.”

Rony Delice, 32, contracted cholera in 2011. He spent time in the hospital, doubled over with agonizing stomach pain and severe vomiting. He is still traumatized from the experience, he said, and expected compensation that never came.

“When I heard about the request for foreign intervention, I said to myself, ‘They were here before and look at the country now,’ ” Delice said. “People were dying when they were here – and they continue to die today.”