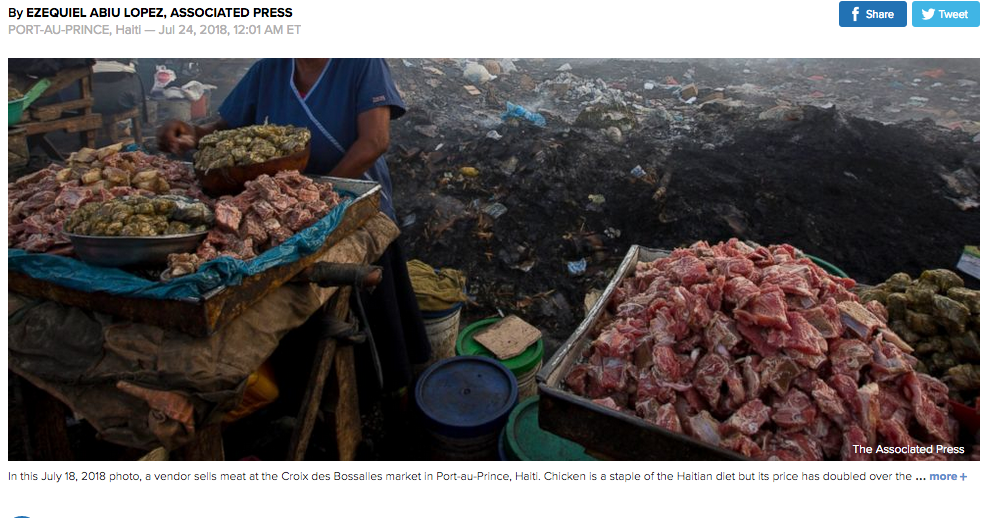

Chicken is a staple of the Haitian diet but its price has doubled in four years. Cooking oil and rice have gone up 10 percent the last 12 months. A liter of milk costs more than half the daily minimum wage, putting it out of reach for most of the country.

The cost of living seems like it is spiraling out of control to many Haitians, making life even more of a struggle in the Western Hemisphere’s poorest nation.

“It’s really hard,” Cassandre Milord, an accountant in a small shop in Haiti’s capital, said of the inflation that has been in double digits since 2014. “You never know how much money you need to go to the market. The prices go up every day.”

It’s a nearly universal complaint across Haiti, and it lies at the root of the four days of deadly protests over steep fuel price hikes that shut down Port-au-Prince earlier this month and raised the specter of the mass unrest that has paralyzed the country in the past. Inflation is a fact of life in much of the world, but amid so much misery it resonates painfully here with everyone from people selling small bags of rice in the street to owners of small businesses — everyone except the tiny elite.

“There’s no money to send the kids to school,” Arceline Charles said as she sat in a crowded downtown street selling eggs from a carboard tray. “The country is a complete disaster.”

The government of President Jovenel Moise, who took office in February 2017 after a messy, contested election, set off protests when it abruptly announced double-digit increases in the prices for gasoline, diesel and kerosene. It was part of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund to eliminate fuel subsidies, to boost government revenue, in exchange for more support from member nations.

Officials may have thought the public would be distracted by that day’s World Cup match featuring local favorite Brazil, but the reaction was explosive: People flooded into the streets, erecting flaming barricades and clashing with police. At least seven people died and dozens of businesses and cars were looted, burned and destroyed.

Prime Minister Jack Guy Lafontant, facing a no-confidence vote in parliament, resigned along with his Cabinet. But the government has yet to explain why it failed to accept the IMF recommendation to enact the price hikes gradually or whether it still intends to comply with recommendations that it modernize its economy by improving tax collection and increase spending on infrastructure, education and social services.

Moise appealed for calm as he looks for a new prime minister. “I can understand the situation facing many of our unemployed compatriots. Hunger and misery are crushing us,” he said in a national address in Creole, the French-based language spoken by the majority of Haitians.

The president, a businessman and farmer who sold himself in his campaign as someone with the knowledge and expertise to lift the country, faces a steep challenge.

Haiti is one of the most unequal countries in the world, with the wealthiest living in walled-off mansions while about 60 percent of its nearly 10.5 million people struggle to get by on about $2 a day. A January report by the U.S. Agency for International Development said about half the country is undernourished.

The fuel price increases, with diesel slated to rise about 40 percent and kerosene about 50 percent, would have rippled through an economy that is largely stagnant. Agriculture, the most important segment, is suffering from a long-standing drought and the devastation caused by Hurricane Matthew to one of the most fertile parts of the country in 2016.

The Central Bank has sought to contain inflation but prices are rising around 16 percent a year. And the bank’s policy of devaluating the currency, the gourde, has in the eyes of many only made the situation worse because Haiti relies heavily on imports.

Even those fortunate enough to work or to own a business find it increasingly difficult to survive. The minimum wage is about $150 a month, far below what is needed to support a family in Haiti.

“It is a situation of massive impoverishment, with many sectors of the middle class becoming poorer and an increasing percentage of people who really can’t eat,” said Camille Chalmers, an economist and director of a non-governmental group that promotes the rights of workers.

Milord, the accountant, said she already spends about a quarter of her daily pay, equivalent to about $3, on transportation and lunch. “Imagine how people get by who only make the minimum wage,” she said.

Business owners say they, too, are feeling the effects. Maxime Cantave, who opened a car wash and adjacent cafe in the Delmas area of the capital, said his business is down by a third over the past two years.

“People don’t have any money,” he said as two vehicles were getting cleaned and the cafe was empty on a recent afternoon, a time when both would normally be full.

Cantave returned to his native country from Florida after the devastating earthquake in January 2010, hoping to take advantage of the surge in international aid and private investment flowing into Haiti as part of the reconstruction. That investment has largely tapered off, hurting him as well as people like Benoit Vilceus, who runs a boutique hotel and a company that does construction and interior design.

Vilceus says his businesses were already struggling but he had to temporarily halt a construction project in the city of Les Cayes because of the recent unrest.

“This has been building up for a long time,” he said of the unrest. “It was just a matter of time.”