PORT-AU-PRINCE – In Haiti, rape has become a weapon of war for gangs. What happens in the hours and days after women and girls are raped can determine their future, but most survivors face insurmountable obstacles before they can start recovering physically and mentally. And that’s if they aren’t raped a second time or third time. Once a woman is raped in Haiti, she faces a maze of other challenges. These are just a few:

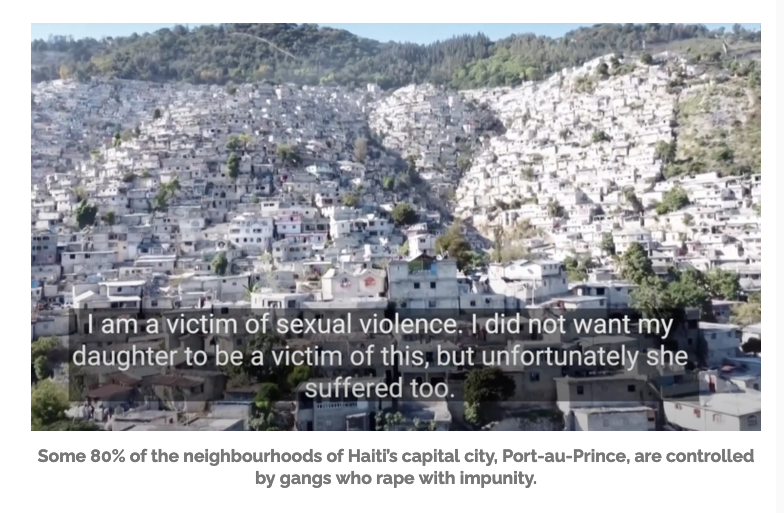

To reach safety, she must first traverse urban areas that have become battlefields. Roughly 80% of Port-au-Prince’s neighbourhoods are controlled by gangs. Hundreds of people have been killed or injured by stray bullets since the start of the year.

Finding transport to reach a clinic or hospital outside of her neighbourhood can be challenging and expensive. Transport options have been reduced due to rolling fuel shortages, inflation, and fears of kidnappings. Prices for some trips have quadrupled in the past year.

Several clinics and hospitals have suspended some of their services or closed due to gang violence; others are full because of the cholera outbreak. Staff shortages are chronic. Although most of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospitals are now open, some are not operating at full capacity. The MSF clinic in Cité Soleil, one of the neighbourhoods most impacted by the gang violence, closed between March and the end of May due to insecurity. The organisation continues to run mobile clinics in some areas.

Prophylactics for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases are usually available. Emergency contraception is also available, but many women fail to reach a clinic within the 72-hour window. Abortion is still illegal in Haiti. For women who can afford it, Misoprostol – sold as Cytotec in Haiti – is often used to induce abortions and can be found in pharmacies or with street-sellers. Follow-up care is another story. Unsafe abortions contribute to Haiti’s high maternal morbidity rate, already the highest in the western hemisphere.

Even if a woman manages to access emergency healthcare, it is less likely she will be given long-term counselling for trauma after rape. Haiti has long had a shortage of mental healthcare workers, and therapy has often been viewed as a luxury most can’t afford when the urgency of basic survival needs are the priority. The social stigma of sexual violence also leads many rape survivors to carry the burden in silence.

Most rapes go unreported, and with good reason. Many police stations have been abandoned after being torched and looted by gangs. Dozens of police officers have also been violently killed or kidnapped by gang members. With little money left in Haiti’s coffers, dozens of officers held protests earlier this year. More than 3,000 have left the force since 2021.

Women often flee their homes and neighbourhoods after rapes. More than 160,000 people have been displaced. With scant government support and a lack of protected displacement sites, some women have reported being raped again in these insecure environments.

Even when Haiti had a functioning government, very few rape cases ever made it to trial. With no remaining elected officials left, many of Haiti’s institutions – including the courts – have screeched to a halt. Clerks are often on strike, and limited governmental funding means many court offices are run down or closed. Although victims technically have access to the justice system, many can’t afford attorneys.

Three survivors from Cité Soleil, a shantytown on the outskirts of the capital that is entirely controlled by gangs, tell their stories. For safety reasons, their names have been changed, but their testimonies (which they voice themselves in the short video clips below) are all too real, and their experiences reflect those of an untold number of women who, just like them, confront impossible challenges and dangers every day just to keep themselves and their children alive.

Kari: ‘We can’t find support. It’s war everywhere.’

Kari, 39, had already lost her baby and her husband to gang violence before she was raped, then later kidnapped. While held captive, she was beaten and raped again repeatedly over three days before being released naked into the streets. She sees no point in reporting any of it to the police. Struggling psychologically and physically from an infection due to the rapes, and trying to look after five children on her own, Kari has received no assistance, bar some food from a local priest and some support from a women’s community organisation.

Kari’s testimony:

First, Kari, a 39-year-old resident of Cité Soleil, lost her baby to a stray bullet. Less than a year later, in June 2021, her husband was shot by criminals while fishing on his canoe. Kari was still trying to recover from those tragedies when the bloody events of July 2022 unfolded.

That month, 10 days of heavy gang warfare in the seaside shantytown left nearly 500 people wounded, missing, or dead; multiple sexual assaults were registered; and 3,000 people fled their homes, Kari and four of her children among them.

“I started to live badly on 8 July 2022. [Gang members] burned my house down and were violent to me. I wasn’t a victim of sexual violence, but they raped a young woman who was living in the house. I lost all my important documents,” she said. Since the death of her husband, Kari had been struggling to meet her children´s needs. She made money selling goods – fish, rice, dried baby shrimps – but the attack of July 2022 left her with nothing. Helpless, she fled the neighbourhood with a group of people. To do so, they had to cross an area called dèyè mi (“behind the wall” in Krèyol), known to be the frontier between two gangs ́ territory. It is also the only way in and out of the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Cité Soleil where she lived.

“As I was walking in dèyè mi with other people because there was no public transportation, men from the area grabbed us and raped us,” she said. “I was also hit by a bullet and my leg still hasn’t healed. When it rains, the pain dominates me.”

Kari spent some time living in the Plaza Hugo Chávez, a public square in the centre of Port-au-Prince where thousands of Haitians fleeing from violence had settled in an improvised camp. She had managed to take a few things from her house to sell, but the precarity of her situation pushed her to leave for the Dominican Republic with her two youngest children, aged 17 and 11. She didn’t last long in the neighbouring country – Haiti and the Dominican Republic share the Caribbean island of Hispaniola – as her children couldn’t get proper schooling there. Three months later, they returned to Port-au-Prince.

Back home, she started trading again, as many women do to survive. On Tuesday 14 March, she took a bus with 16 other women she used to sell products with. Their destination was Arcahaie, a town 25 miles northwest of the capital. Travelling out of Cité-Soleil is not safe, but Kari didn’t have a choice. Business had started to slow, and she had borrowed the equivalent of $140, only managing to give $18 back.

“While I was going to Arcahaie, arriving at Source Matelas (a neighbourhood north of the capital where there have been a series of violent gang raids in the past few months), people stopped the bus I was on and ordered us to get down and follow a funeral,” Kari said.

After the funeral, she and other women were kidnapped by the men who had forced them out of the bus.

“We entered a house. They asked for our identification documents. I told them that I had come to sell, that I had no ID with me,” she said. “They pushed us and said that we surely live in the area of Ti Gabriel (one of Cité Soleil´s gang leaders). ´You are thieves, we are going to kill you,’ they told us.”

The men kept them captives for three days, beating and raping them repeatedly.

“They did everything they shouldn’t do to us,” Kari recalled. “When I was still conscious, I counted seven men. I am asthmatic, and although I had an asthma attack, they kept beating me,” she said.

She ended up passing out, but that didn’t stop her assailants either.

“When I regained consciousness, I saw young men who could have been my children raping me. I told them: ´If you want to kill me, you can do it, even if I have young children; God will continue to watch over them. It’s better to kill me.’”

During those three days, the women had to do the gang members‘ laundry. They barely ate. The men constantly told their captives they would kill them and continued to rape them, until the fourth night came.

“After all that, they changed the dialogue and asked us if we wanted to stay with them. I told them that I have four children without a father. We spoke to them at length. In the end, they released us, naked. As we left, people of goodwill in the area gave us clothes to put on.”

It took Kari eight hours to reach her mother for help. Kari´s mother bought medicinal leaves to take care of her wounds. The window to take medication to prevent unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases is 72 hours, but 15 days passed before a friend convinced Kari to go to the hospital. There, she received medication for an infection, but she still hasn’t fully recovered.

Kari hasn’t been to the police to file a complaint. She doesn’t believe it will make a difference. “There is no justice,” she said.

Since the kidnapping, Kari lives in extreme poverty. The gang members stole all the goods she planned to sell, which means she has no money to resume her business. She still has to pay her debt and is now also responsible for her fifth child as well – a six-year-old girl who hadn’t been living with her before.

Kari doesn’t have enough money to pay for rent, so they live in a camp set up in a school. When it rains, they must spend the night standing or sleep under the water. To eat, they depend on a priest who distributes food; for water, they rely on rain. Pressed by their desperation even for basic food needs, her 20-year-old son, the eldest, dropped his studies to go fishing. Kari blames authorities for her situation, and for leaving her no other option than risking her life to survive.

“We, who are from Brooklyn, have never had the Haitian state saying ‘no, [these violent attacks] shouldn’t take place. If we had enough money, I don’t think we would be in the streets. We know that if [the gang members] take us, they will kill us.”

Since the rape of last March, Kari has been struggling psychologically. The only support she has found is at the women’s organisation Nègès Mawon. But in the past few weeks, the rise in gang-related violence has prevented her from reaching the organisation, which is located in a neighbourhood out of Cité Soleil. She says she feels ashamed of what happened to her, and can´t overcome the trauma of her assaults.

“I intended to hurt myself because I saw that I was living in bad circumstances. The violence I suffered in Source Matelas is the one affecting me the most,” she told The New Humanitarian.

When she remembers what happened to her, she can’t hold back her tears.

“I was a fat person; I became small as you see me. They took my business; they beat me, and they raped me”, she said. “I demand justice from [the authorities]. We who are unfortunate are asking for more security. In Cité Soleil, we suffer more. We can’t find support; it’s war everywhere.”

Madeline: ‘My mother keeps crying – she doesn’t see what she is going to be able to do.’

Madeline, 16, was heading home to Cité Soleil after trying to make some money reselling food in the city when armed men stopped her bus, killed some people on board, and took others hostage. Raped and beaten, she found herself covered in blood when she regained consciousness. An unknown number of men raped her over several days before she was released, again, naked. Later, at hospital, she learned she was pregnant from the rape. Feeling trapped by the rising tide of gang violence and the possibility of being raped again, Madeline has repeatedly tried to take her own life.