A week after U.S.. government officials informed an Orlando gun shop owner that his request to export semi-automatic weapons, ammunition and ballistic armor to Haiti had been denied, the federally licensed arms dealer fired off an email to a Pompano Beach ballistic armor company and requested personal protection gear on behalf of Haitian police.

The police chief in Haiti was concerned about a recent militant attack on a police station and he needed some light weight ballistic gear for some of his officers, Junior Joseph wrote in the May 17, 2016 email to Kevin Beary, the director of business development at Point Blank Enterprises. Informed of the request, Beary’s boss responded with some budget-friendly suggestions and said “remember, export licenses are required for Haiti..”

“We already have an export license,” Joseph emailed back.

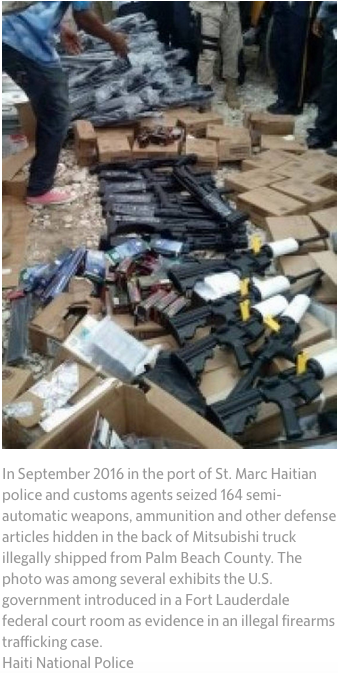

It was a lie, say federal authorities, who accuse Joseph and his brother Jimy of conspiring to ship firearms and ammunition from the U.S. to Haiti without a license. The firearms were concealed in a white Mitsubishi Fuso commercial work truck that had been shipped from Palm Beach County, and arrived in the port of Saint Marc on Aug. 30, 2016 aboard a Monarch Shipping Lines freighter.

The owner of Global Dynasty Corps., LLC in Orlando, Junior Joseph is currently on trial in Fort Lauderdale, where government prosecutors say he and Jimy, whose own trial is scheduled to start next week, concealed 159 semi-automatic single- and double-barreled 12-gauge shotguns, five AR15s and two 9mm Glock 17 pistols inside the truck and illegally exported them to Haiti. Also hidden in the vehicle were tactical vests, police boots and more than 25,000 bullets including shells for the shotguns.

The case could go to the jury as early as Friday, and Junior, like Jimy, potentially faces a long prison sentence if convicted. The most serious charge, conspiracy to export fire arms without a license, carries up to 20 years, a $250,000 fine and three years of supervised release..

While the illegal arms trafficking case is unfolding in a Fort Lauderdale federal courtroom, it spotlights the failure of the U.S. arms embargo on Haiti and the lack of political will in that country to suppress the illegal arms trade. Despite the arms embargo, which was first put in place after the 1991 coup that ousted then-elected Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti is awash in illegal weapons, with politicians long accused of funneling arms to gangs while others are being protected by armed militias.

A recent uptick in violence by gangs in many Haitian neighborhoods forced both the U.S. State Department and the government of Canada to revise their travel warnings for citizens wishing to visit the country. Their concerns were shared by the United Nations, whose current head of missions told the Security Council in December that the mission was investigating reports that armed gang members, dressed as police officers, had carried out a massacre in the impoverished neighborhood of La Saline.

of Canada to revise their travel warnings for citizens wishing to visit the country. Their concerns were shared by the United Nations, whose current head of missions told the Security Council in December that the mission was investigating reports that armed gang members, dressed as police officers, had carried out a massacre in the impoverished neighborhood of La Saline.

Arriving a month before Haiti’s high-stakes do-over presidential elections, the Saint Marc weapons seizure on Sept. 8, 2016, immediately raised concerns, with Haiti’s interim government at the time questioning who was behind the shipment and who the firearms were intended for. Parallel investigations were launched. A Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives agent flew to Port-au-Prince to inventory the guns and begin a trace on the weapons that eventually led investigators back to Junior Joseph’s Orlando gun shop. Haiti’s judicial police also began interviewing port employees, trying to find out who is responsible for the arms and what happened to the pistols that arrived in two empty 9 mm Glock 17 boxes.

Police investigators would learn that Jimy Joseph twice tried to clear the truck from customs after he arrived in Haiti from Miami on Aug. 29, but failed. His efforts were later joined by that of a woman, Sandra Thelusma. Two days before the seizure, Thelusma raised suspicions among customs agents when she tried, and also failed, to get agents to release the Mitsubishi without verifying its contents.

In the conclusion of their report, police investigators asked that a Haitian judge issue arrest warrants for Thelusma, who later turned herself in, Jimy Joseph and Charles Durand, a cousin of Joseph’s who had accompanied him from Orlando to Palm Beach County to ship the truck, and in the process, listed himself as the shipper.

Durand, who isn’t charged in the U.S. but faces deportation after overstaying his visa, testified in court that he was asked by Jimy Joseph to help him load the truck with boxes, but he had no idea of their contents.

In addition to Thelusma, a Haitian Investigative Judge, Dieunel Lumeran, who later received the case, charged eight others with a range of crimes including illicit firearms and ammunition trafficking, forgery and money laundering.

Among those charged: Several former government officials in president Michel Martelly’s administration including Godson Orélus, the police chief, and Vladimir Paraison, Orélus’ one-time police director for the West region. A confidante of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse., Paraison reportedly fled the country after Judge Lumeran issued an arrest warrant and he was dismissed as the coordinator of the president’s palace security.

Orélus, meanwhile, remains in jail in Saint Marc. He recently appealed his arrest and incarceration by Lumerant, who denounced what he said is an assassination attempt after his home was riddled with bullets in the middle of the night.

So far only the Joseph brothers are charged in the U.S. case. But during court testimony, the names of Orélus as well as that of the head of the police academy, Francène Moreau, and a Haitian senator, Herve Fourcand, have all come up. For instance, among the documents that Junior Joseph presented to U.S. officials when he applied for export licenses at the State Department and the Department of Commerce was a Haitian National Police weapons import certificate signed by Orélus.

Junior Joseph’s defense attorney, Robert Berube, has attempted to separate his client from Jimy, noting that Junior Joseph is a former U.S. marine who runs a tight ship as a federally licensed firearms dealer and the head of Global Dynasty Corps., LLC. He noted that he was cooperative when ATF agents arrived with a search warrant and asked for the logs detailing all of the guns that his store had acquired and sold.

During the search, agents found boxes of ammunition and a business card binder with contact information for Moreau and Fourcand, among others. They also transferred data from Junior’s IPhone.

“It’s not shocking or surprising a gun store would have ammo on site?” Berube asked ATF special agent Robert Shirley during cross examination.

Shirley, who had brought examples of the smuggled gun to court to show the jury what they looked liked, replied, “No sir.”

During the search of Global Dynasty, agents also found correspondence describing Junior Joseph as the vice president of the company’s Haiti affiliate, Global Dynasty, S.A..

“He goes back and forth. His father was in the Haitian military for 25 years,” Berube said during the cross-examination of another ATF agent, Sarah O’Connor, who had identified the business cards of Fourcand and Moreau during her direct testimony. “He has a lot of friends in Haiti.”

“He does,” O’Connor responded.

The government has tried to show that Junior Joseph not only talked about expanding his firearms and accessories business into Haiti but he also took steps to do so with his brother Jimy..

Anderson Sullivan, a government witness and Homeland Security Investigator, testified that not only did the brothers travel to Haiti together as late as April 14, 2016, according to airline records, but when Jimy Joseph traveled on a one-way ticket from Miami to Port-au-Prince on Aug. 29 “history data indicates that the purchase was made by Junior Joseph.” The trip occurred a day before the shipment’s arrival into Saint Marc..

In addition to the airline records, the government also highlighted WhatsApp conversations that Junior had about the shipment with Fourcand, the senator, and his brother, and someone identified on his phone as Edouard, a friend of the police chief.

According to the indictment, several weeks before the truck’s Haiti arrival, Junior Joseph sent a Haitian politician copies of the Monarch shipping documents for the Mitsubishi shipment via WhatsApp. He also sent copies to someone associated with the politician.

While Fourcand hasn’t been indicted, O’Connor and Sullivan both met with him at Miami International Airport during on one of his visits to the U.S., and questioned him in connection with their investigation.

Beary, the former business development director at Point Blank, testified that he had met with Fourcand at an Orlando church at the request of Junior Joseph on March 3, 2016. Beary, a former Orange County sheriff, said Junior Joseph had mentioned that “he had some contacts with Haitian leadership,” and spoke of selling ballistic vests and other police equipment in Haiti.

“He was friends with the police chief… and was talking about opening a storefront in Haiti,” Beary testified.

As part of his license applications to the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Commerce, Junior Joseph said he was proposing to provide a $27.6 million security training program for the Haitian police, its police academy and private security contractors in Haiti. The end user would be Global Dynasty, S.A., a company that the Haitian police investigative report noted in October 2016 only existed on paper.

One license was to be able to provide the training and defense materials, regulated by the State Department. The other was to export $8.5 million worth of hardware including 25,000 shotgun shells, 500 vests, 50 shotguns, pepper spray and Tasers.

Though the importation of shotguns into Haiti are controlled by the U.S. and the Haiti National Police does not use Tasers, a license was issued anyway by the Department of Commerce on April 1, 2016, for various items to be exported to Global Dynasty Corp., S.A. in Haiti.

About a month later, on May 5, Commerce revoked its license after the State Department denied Junior Joseph’s technical training agreement. Junior Joseph was officially notified in a letter dated May 10, 2016..

“We denied it because we could not verify thebona fidesof the transaction,” Alex Douville, an analyst with the Department of State Defense Trade Controls, testified. Douville said that when the State Department contacted the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince, officials reported that the Haiti National Police “and government denied they had any contract with Global Dynasty Corp.”