By Hugh Locke

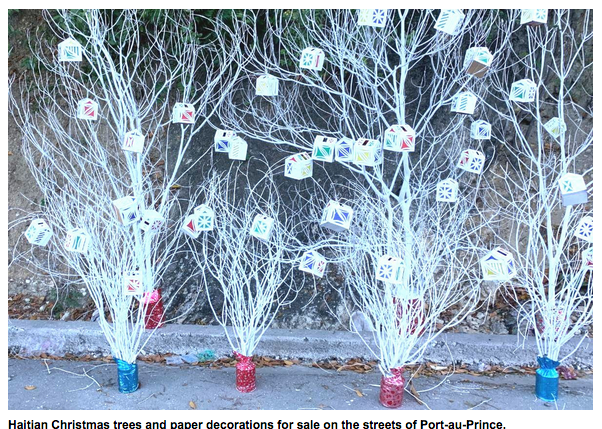

An uneasy calm has descended over most of Haiti for the past few weeks. The underlying issues that led to months of protests and a national lockdown, known here as peyi lòk, remain unresolved. But all sides have suspended operations for the moment. This is not the result of any formal negotiation between the fractured government and opposition camps. Instead, it seems as if everyone involved in the conflict just needed a break for the holiday season and decided at the same time to back down. The result has the eerie quality of a Christmas truce, with the streets suddenly bustling with festive preparations. People are once again complaining about traffic jams in the capital, secretly pleased to be doing so after being locked in their homes since September. The mood is tempered, however, by the unquestioned knowing that massive anti-government protests are almost certain to resume early in the new year.

I would like to conclude by introducing a new term “rational optimist” to the development lexicon. This I apply to those from the business, non-profit, institutional and government sectors who have weathered peyi lòk, who know there is still more political and economic upheaval to come, but who nevertheless remain resolutely committed to staying the course to be part of building a prosperous and equitable future for Haiti.

|

|