On Oct. 2, the United Nations Security Council authorized yet another armed intervention in Haiti. This new effort, aimed at breaking the stranglehold of paramilitary-style gangs in Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince, will not be an official U.N. peacekeeping mission. Instead, it is being organized and funded directly by the United States, with 1,000 police officers from Kenya slated to take the lead on the ground.

On Oct. 2, the United Nations Security Council authorized yet another armed intervention in Haiti. This new effort, aimed at breaking the stranglehold of paramilitary-style gangs in Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince, will not be an official U.N. peacekeeping mission. Instead, it is being organized and funded directly by the United States, with 1,000 police officers from Kenya slated to take the lead on the ground.

The mission is nominally being undertaken at the request of the government of Haiti’s de facto president, Ariel Henry, who was neither elected nor officially appointed to any position in the government. Henry, a leader in the anti-Aristide coalition in the buildup to the 2004 coup, had been nominated as prime minister—the No. 2 position in the Haitian government—by then-President Jovenel Moïse days before Moïse was assassinated in his home in July 2021.

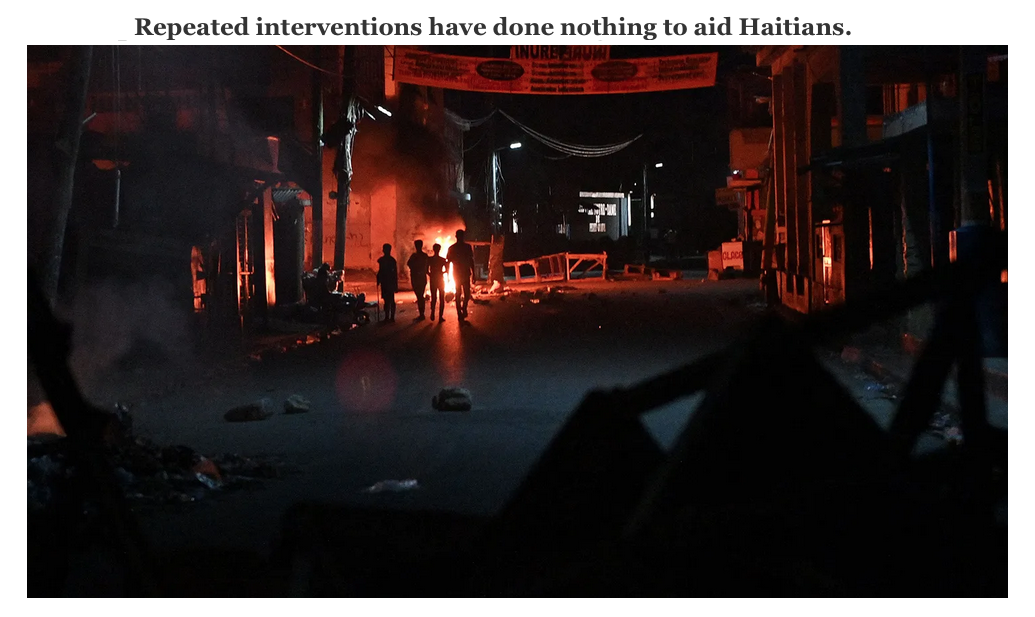

He was never ratified by Haiti’s parliament because there was no parliament to ratify him—Moïse had let every legislator’s term lapse by refusing to organize elections. There are, in fact, no elected officials in Haiti at all as of right now. Henry assumed the acting presidency after Moïse’s assassination at the direction of what is known as the Core Group, which includes representatives of the United States, the U.N., and other powerful countries. As chaotic and brutal as the situation on the ground is, every intervention in Haiti in the past has done little but make things worse.

Kenya’s High Court is expected to rule on whether the mission can proceed on Thursday. If approved, it will be the seventh U.S.-sponsored intervention into Haiti since the country won its independence from France in 1804. The biggest and longest was the brutal U.S. Occupation of Haiti (that was its official name) that began in 1915 and ended in 1934. The most recent direct U.S. invasion came in 2004; the initial U.S.-led force was replaced, at Washington’s request, by a U.N. peacekeeping mission that remained until 2019. During that period, the United States also sent more than 22,000 troops and an aircraft carrier group, the USS Carl Vinson, to Haiti to maintain security and prevent a migrant exodus after the catastrophic 2010 earthquake.

A historic photograph of U.S. Marines marching in front of palm trees.

U.S. Marines march in Haiti, circa 1934. Bettmann Archive/via Getty Images

In all, the U.S. military and its proxies have been in Haiti for at least 41 of the last 108 years, always in the name of securing peace, political stability, and human rights—and never actually succeeding in doing so.

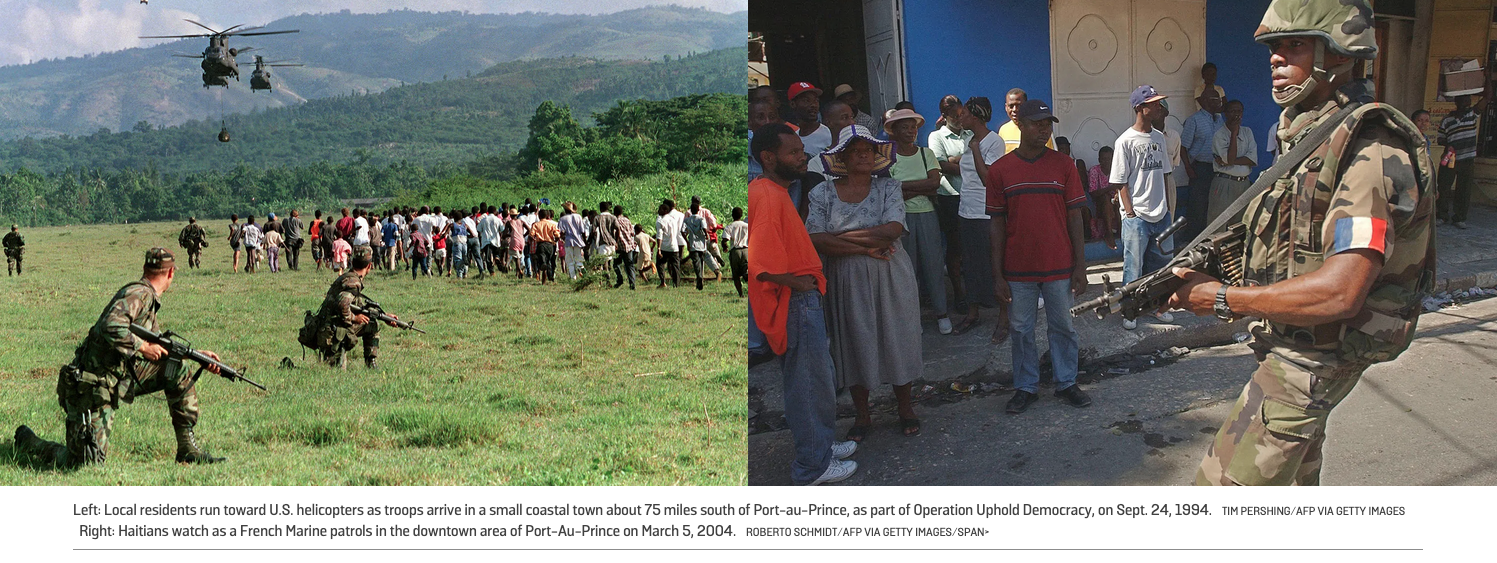

Yet the only lesson Washington seems to have learned in that time has been to outsource as much of the dirty work as possible. For a 1994 U.S. invasion dubbed Operation Uphold Democracy, aimed at restoring recently overthrown President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, then-U.S. President Bill Clinton got a U.N. Security Council authorization and assembled a nominally multilateral security force consisting mostly of Americans along with a handful of troops largely from Caribbean nations to handle the expected cleanup.

The next U.S. intervention, in 2004, was meant to stabilize the unrest brought on by another successful coup against Aristide, carried out by groups with ties to the George W. Bush administration. This time, the invasion itself was multinational, with French, Chilean, and Canadian troops arriving alongside the U.S. Army and Marines. Months later, the force was replaced by the U.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti—known in French by the acronym Minustah—led by the Brazilian army. After two years, it managed to set up new, relatively fair presidential elections. But the forces remained for another 15, as mission creep set in and political stability remained out of reach.

Minustah was explicit outsourcing on the United States’ part; the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) used it as a cost model for outsourcing foreign interventions. “Conducting a U.S. operation similar to MINUSTAH would cost the United States about 7.5 times as much as its official contribution to the UN for that mission,” GAO analysts noted in a 2006 report, in part because “it would be subject to higher operational standards.” Those lower operational standards were evident: Minustah is best known for killing civilians, crushing political protests, fathering and abandoning children with Haitian women, and starting and trying to cover up its role in a deadly cholera epidemic that is still killing Haitians to this day.

The newest mission takes outsourcing to a new level. While it was approved under Chapter 7 of the U.N. Charter (“action with respect to threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression”), it will not be the responsibility of the U.N. Department of Peace Operations. Instead, it is being dubbed a Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission, which seems to be an entirely novel term. It will have a “lead nation”—Kenya—as well as troops from other nations: Jamaica, the Bahamas, and tiny Antigua and Barbuda, to start.

The “breaches of the peace” in Haiti are being committed by paramilitary criminal gangs that dominate the capital, Port-au-Prince, and other cities. María Isabel Salvador, the U.N. special envoy for Haiti, told the Security Council that she receives daily reports of murders, rapes, and kidnappings. In October, heavily armed men wearing police uniforms abducted the head of the High Transitional Council, a government body charged in part with organizing the first elections in Haiti since 2016.

A citizen vigilante movement known as “Bwa Kale” has attacked the gangs, with at least 395 alleged gang members lynched across all 10 of Haiti’s departments, Salvador said. Some observers have noted that it may become a gang in itself. (“Bwa Kale” is literally Haitian Creole for “bare wood,” or, figuratively, an erection; it is used in slang to mean “no mercy.”)

This terror has all but paralyzed the capital. With parents unable to work or shop, the number of children suffering from “severe wasting”—the most lethal type of malnutrition—has risen 30 percent to more than 115,000 in the last year, according to UNICEF.

The armed mission’s costs, according to the U.N., “will be borne by voluntary contributions and support from individual Member States and regional organizations”—principally the United States, which has already pledged $100 million for “logistics, including intelligence, airlift, communications and medical support,” The Associated Press reported.

In other words, not only is the United States outsourcing this mission to the U.N., but the U.N. is outsourcing it back to the United States—which is then further outsourcing it to Kenya, which in turn is outsourcing some parts of its mission to Haiti’s Caribbean neighbors. (Got all that?) The United States also partially outsourced its sponsorship of the Security Council resolution to Ecuador, whose right-wing, pro-American president, Guillermo Lasso, has few friends in his own country and needs all the foreign support he can get.

Kenya was not the Biden administration’s first choice to lead the intervention. For months, the State Department tried to lean on Canada to take the reins, leaking to the press that the Security Council resolution “was drafted on the hope and expectation that Canada would lead the effort.” White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan felt confident enough to lean over his skis and say Canada had “expressed interest in taking on a leadership role.”

Police officers patrol a neighborhood in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Police officers patrol a neighborhood amid gang-related violence in downtown Port-au-Prince on April 25.Richard Pierrin /AFP via Getty Images

That was always wishful thinking. As CBC News has reported, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government, “unwilling to give a flat no to the many countries asking it to save the day, used a variety of tactics to stall for time. It sent fact-finding missions to assess conditions on the ground, convened parties for talks, set conditions that were unlikely to be met and never missed an opportunity to remind the world that past interventions had not produced good results.” In March, ahead of President Joe Biden’s visit to Ottawa, Trudeau told reporters: “Outside intervention, as we’ve done in the past, hasn’t worked to create long-term stability for Haiti.”

Then the Americans turned to Brazil, only to be turned down. Current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was also in power in 2004 when his country assumed control of Minustah. Though, at one point, Lula called it “the noblest humanitarian mission ever carried out by the Brazilian Armed Forces,” the intervention became a scandal in Brazil, especially among leftists, who remember it for the role Brazilians played in a 2005 massacre in the Cité Soleil slum, as well as the suicide of a Brazilian force commander at Port-au-Prince’s Hotel Montana shortly thereafter.

That left Kenya. The East African nation has participated in U.N. peacekeeping missions in at least 29 countries since the 1990s, including the former Yugoslavia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Yemen. But it has, as its defense ministry website states, “remained cautious of involvement in peace operations that have had an enforcement element.” That is with the notable exception of Kenya’s neighbor, Somalia, where the Kenyans have participated in U.N.-endorsed African Union peacekeeping missions since 2012.

Washington wooed Kenyan President William Ruto with the promise of funding for the mission as well as a five-year defense cooperation agreement, offering unspecified support in Kenya’s ongoing war against the Islamist militant group al-Shabab, which is based in Somalia. Even then the East Africans seemed reticent; it was Nairobi, it seems, that insisted on a largely symbolic Security Council mandate, to give the mission a stronger patina of international legitimacy.

In a speech aired after the Security Council session, Ruto called the mission an act “of solidarity with the African Diaspora, in observance of our sacred duty towards our own flesh and blood, carried into captivity to suffer in chains.” He invoked the legacy of both the Haitian Revolution and the devastating decades-long extortion imposed on Haiti’s post-independence governments by France.

Many refugee tents are seen in Port-au-Prince

Tents are seen in the courtyard of the Vincent Gymnasium, home to refugees from the gang war, in Port-au-Prince on Oct. 5.Steven Aristil/Anadolu via Getty Images

But although Ruto’s high-minded words may be sincere, there is also a clear economic incentive: As the Kenyan defense ministry website notes, “UN peace operations offer Kenyan soldiers and police a rare opportunity to obtain UN allowances that are ordinarily not offered by the KDF [Kenya Defence Forces]. … Due to the huge sums involved, remittances—including from peacekeepers—are now being recognized as an important contributor to the country’s growth and development. … This enables the KDF to build, equip and train a significant proportion of its forces.” While this mission will be financed by the United States instead of the U.N., that structure will likely remain.

If the relevant Kenyan officials sign off on the mission, the people of Port-au-Prince may not feel Ruto’s promised solidarity for long. In Somalia, the Kenyan military also operated an extensive smuggling ring in sugar and charcoal that not only lined Kenyan pockets but provided a financial lifeline to its purported enemies in al-Shabab. This racket enjoyed “the protection and tacit cooperation of leaders at the highest echelons of the Executive and the National Assembly,” according to the watchdog group Journalists for Justice. Once again, “lower operational standards” may take a toll.

Haitians have long had to deal with their own corrupt and vicious police. Many of the gangsters who are preying on Port-au-Prince came from within the ranks of the Haitian National Police, or PNH. That includes the most internationally notorious of them, Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier, who before becoming leader of the self-styled Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies gang had been a member of the PNH’s specialized anti-gang task force. This is part of the reason why an international mission explicitly formed to support and further arm the Haitian police, along with an expanded arms embargo guaranteeing that the PNH and the MSS will have a complete monopoly on violence, could easily backfire.

The intervention is thus likely to end up solidifying the power of one gang—if it works at all. Haiti’s gangs are widely known to have operational ties to leading politicians and members of the Haitian economic elite, while Henry, the unelected leader backed by the United States, has been accused by Haiti’s chief prosecutor of participating in the plot to assassinate the former president.

I don’t know who will end up benefiting most from this intervention. But the least likely to benefit will be ordinary Haitians, in whose names these powerful figures are claiming to act.

Jonathan M. Katz is a journalist. He is the author of The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster and Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. His newsletter, The Racket, can be found at https://theracket.news/.