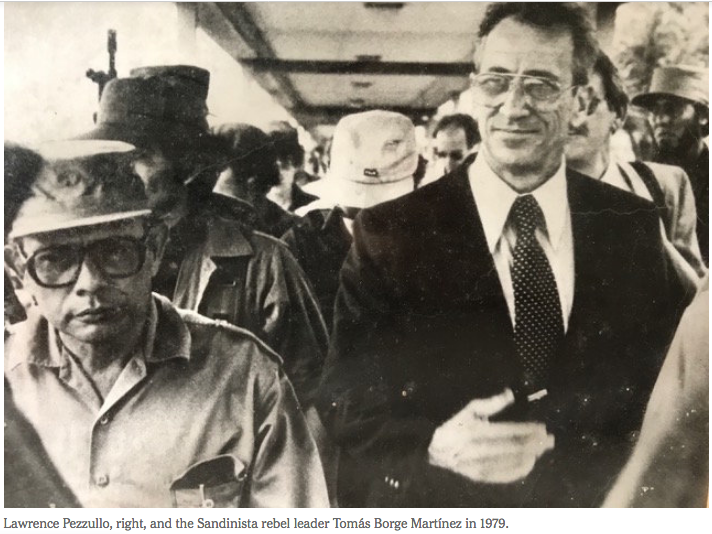

Lawrence A. Pezzullo, an American diplomat who in 1979 negotiated the abdication of Anastasio Somoza DeBayle as leader of Nicaragua and the demise of the dictatorial dynasty that had led the country with Washington’s sponsorship for four decades, died on Wednesday in Baltimore. He was 91.

The cause was heart failure, his son Ralph said.

Mr. Pezzullo also tried, though less successfully, to negotiate a return to civilian rule in Haiti in the 1990s, and he ran the international Catholic Relief Services for a decade. But he is best remembered as a voice of the Carter administration’s commitment to human rights, an effort that culminated in Somoza’s departure.

As the incoming United States ambassador, Mr. Pezzullo was sent to Nicaragua with a challenging mission: to persuade Somoza to avoid further bloodshed in his country’s protracted civil war with the leftist Sandinistas by relinquishing power to them and fleeing into exile, initially in Miami.

Somoza, whose family had led Nicaragua since the mid-1930s, was first elected president in 1967 and gained a reputation for widespread corruption and brutal repression of dissenters. But he was supported by the United States because he was fervently anti-Communist.

A blunt, Bronx-born former teacher and fluent Spanish-speaker, Mr. Pezzullo began almost daily negotiations with Somoza in late June 1979.

“I said that the only way we could begin the process of putting the house together again was for him to go,” Mr. Pezzullo told The New York Times in 1981. “He then played the role of the injured party, that history had played him a bad turn. But eventually he went.”

The Sandinistas seized power less than a month after Mr. Pezzullo arrived, and they remain one of the country’s leading political factions. Somoza was assassinated in 1980 by Argentine revolutionaries near his home in Paraguay.

“Faced with the inevitability of change here,” Mr. Pezzullo said in Managua, the capital, in 1981, “we began to build a relationship with the new regime without agonizing too much about what the future would bring.”

The new envoy symbolically abandoned the ambassador’s home, a palatial, white hilltop emblem of Washington’s dominion over Nicaragua. He chose more modest quarters.

Appointed by President Jimmy Carter to advance his administration’s human rights agenda, Mr. Pezzullo worked with the United States special envoy William D. Bowdler to win the respect of the Sandinistas by accepting the political reality of their military and political success.

He repeatedly went to Washington to lobby the administration and Congress for American humanitarian and economic support for the new government — aid that could provide leverage over the Sandinistas. But as the Sandinistas emulated Cuba’s agenda in advancing a regional socialist revolution against authoritarian governments, his arguments were greeted with growing skepticism in Congress.

“Our problem with the revolution is not that it wants to bring change to a society that sorely needs change,” Mr. Pezzullo was quoted as cautioning Sandinista leaders. “But if that policy parallels Cuban policy, this is going to be very difficult for us to accept.”

After being retained for several months by the incoming Reagan administration, he was recalled to Washington in 1981 after the White House accused the Sandinistas of smuggling arms from the Soviet bloc to leftist guerrillas in nearby El Salvador and of terrorizing dissident Nicaraguans.

Photo

Lawrence Pezzullo in an undated photo. Credit U.S. State DepartmentOn leaving Managua, Mr. Pezzullo drew praise from the revolutionary junta.

“Pezzullo has been the best U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua in this century,” Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, the foreign minister, said. “He tried to help his government understand the irreversibility of the process here and seek a modus vivendi with us.”

The White House later secretly financed a rightist counterrevolutionary militia, the Contras, in its effort to overthrow the Sandinista government in another civil war. That conflict ended with a government promise of free elections, in 1990. In the first peaceful transition of power in five decades, the Sandinistan incumbent president, Daniel Ortega, was defeated. (He returned to the presidency in 2006 and was re-elected in 2011.)

President Bill Clinton named Mr. Pezzullo the administration’s special envoy to Haiti in 1993, with the aim of brokering a transition from the military government to a democratically elected one. Two years earlier, the Haitian president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was overthrown in a military coup.

Mr. Pezzullo and his United Nations counterpart, Dante Caputo, drafted an accord in July 1993 on Governors Island in New York between Mr. Aristide and Lt. Gen. Raoul Cedras, the leader of the Haitian military.

The agreement granted amnesty to government soldiers who had tortured Mr. Aristide’s supporters and allowed the military to remain in power until Oct. 30, when Mr. Aristide was to create a broad coalition intended to temper what was viewed as his Marxist-leaning radical liberation theology.

But General Cedras refused to quit, and Mr. Pezzullo, accused by critics of coddling the military and tolerating its human rights abuses in an ambivalent effort to restore Mr. Aristide to power, was forced to step down. The junta capitulated in 1994, faced with the threat of a United Nations-sanctioned invasion by United States troops.

Lawrence Anthony Pezzullo was born on May 3, 1926, to Lorenzo Pezzullo, who owned fruit stands and butcher shops, and the former Josephine Sasso. He attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, served in the Army from 1944 to 1946, part of the time in Italy, and earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Columbia University in 1951.

He taught school for six years in Levittown, on Long Island, then joined the foreign service and earned a master’s degree from the National War College in Washington.

Over the years the State Department assigned him to Mexico, South Vietnam, Bolivia, Colombia and Guatemala. He was deputy assistant secretary of state for congressional relations before serving as ambassador to Uruguay from 1977 to 1979.

Besides his son Ralph, Mr. Pezzullo is survived by his wife, the former Josephine DiMattia; another son, David; a daughter, Susan Pezzullo Johnston; and seven grandchildren.

He was named executive director of Catholic Relief Services in 1983 and ran it for 10 years. He left amid concerns that the agency was not funneling aid fast enough to drought-ravaged Ethiopia, though he said that his critics, mainly former employees, had not taken into account the agency’s long-term efforts there.

Mr. Pezzullo advocated a pragmatic, flexible foreign policy during his years in government. In 1980, he expressed concern that the incoming Reagan administration would reflexively treat all revolutionary movements as Soviet-sponsored vehicles for world communism.

“The moment you pigeonhole someone, you start building your argument to fit your conclusions,” he said in 1981.

“My basic feeling about a revolutionary movement is that you’d better move with it and live with it,” he added. “And if you’re going to exert influence, exert it in the process of living with it.”