As a cultural area studies graduate, seldom do I feel over my head culturally. Standing in the home of possibly the next Nobel Prize recipient for Literature in Port-au-Prince recently, I found myself way out of my league. One ambassador had cautioned me to “have an intellectual translate” for me. Luckily, when I met the legendary Franketienne, he spoke to me in English. Several weeks later I caught up with him again at the Brooklyn Public Library for an outstanding performance and continued to learn more about this great mind.

As a cultural area studies graduate, seldom do I feel over my head culturally. Standing in the home of possibly the next Nobel Prize recipient for Literature in Port-au-Prince recently, I found myself way out of my league. One ambassador had cautioned me to “have an intellectual translate” for me. Luckily, when I met the legendary Franketienne, he spoke to me in English. Several weeks later I caught up with him again at the Brooklyn Public Library for an outstanding performance and continued to learn more about this great mind.

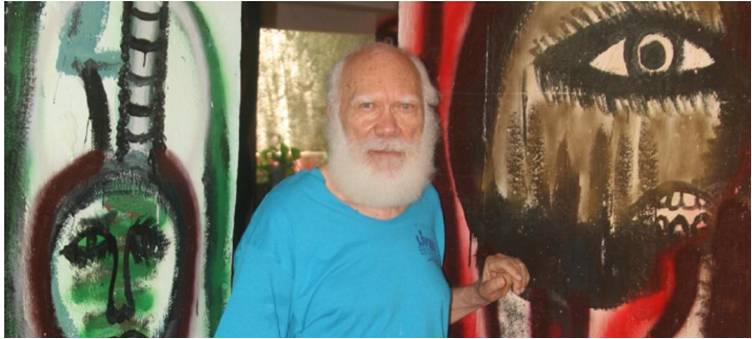

Franketienne was born Franck Etienne in 1936. He is an author, poet, playwright, musician, and painter. Although he speaks English, he has written exclusively in both French and Creole. As a painter, he is known for his colorful abstract works, often emphasizing the colors blue and red, as I saw first-hand in his home. As Emmanuel Duogene told me, “he’s a magician – he works miracles!”  Haunting imagery, surrounded often in red and blue, adorns the walls of his home.

Haunting imagery, surrounded often in red and blue, adorns the walls of his home.

As I delved into his world, I found terrain that was at once foreign and strangely familiar. For example, Franketienne’s fascination with the tragic clown. According to one scholar, the author’s use of this figure creates for the reader a hybrid creature that combines the semi-tragic circus figure of Giulietta Masina’s waif in La Strada, and the “lewd Voodoo (vodou) spirit, the Guede, obsessed with sex and death. In the words of another, “This larger-than-life actor refuses to be silenced.” Having several friends in Haiti who are vodou priests, I have some concept of what this means.

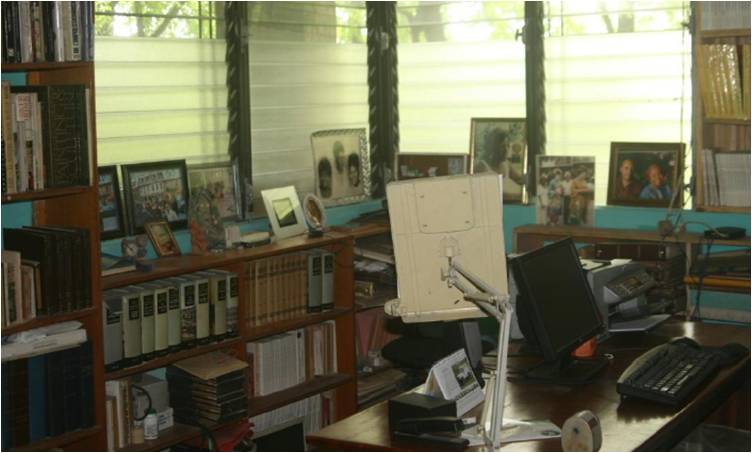

Inside the master’s study, although he writes in a tiny space in a small bedroom.

Inside the master’s study, although he writes in a tiny space in a small bedroom.

Franketienne himself is a larger-than-life protagonist who never stepped down from the national stage in fear of the dictator of the decade. The author likens the artist in a dictatorship to a sado-masochistic relationship in which the slave serves the master. Without the slave, the other cannot play master. A master must have a slave to exist. It is this knowledge that strengthened his resolve through the dark days of Papa and Baby Doc. He specifically did not compare the relationship to Haiti’s historic slavery, however even there, masters needed slaves – but slaves were expendable due to their numbers.

The author has painted or otherwise decorated every remaining surface in his home.

The author has painted or otherwise decorated every remaining surface in his home.

Franketienne believes, as did Jacques-Stephen Alexis, that creative works should represent the daily reality of the people. One of my favorite authors in Indonesia, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, had this same thought. As one expert has said, as the Franketienne reality is closely linked to Vodou rituals and close relations with the gods of the Vodou pantheon, they must by definition be associated with the artistic process.

As Alvina Ruprecht of Carlton University states:

Transplanting into theatrical language the phantasmatic world of the artist living under the Duvalier regime, the poet/actor has produced an apocalyptic scenario where deformed creatures and power-hungry voices taunt the playwright and drive him mad, evoking an encounter with Death – the Baron Samedi, a spirit of the Vodou pantheon. Like the gangs of “good for nothings who roam the streets of Port-au-Prince.” Evil spirits – the “Gran makout” – take control of the torturer, the sadistic and uncultured, and sexually-ravenous brute who wants to silence the artist.

Franketienne visited Japan as a guest of Marcel Duret, the then Haitian Ambassador to Japan, where he witnessed Kabuki. The author seems to have absorbed Japanese theater into his later works. My father was a translator of the scatological writer Louis-Ferdinand Celine, so I am unfazed by some of Franketienne’s writings:

With much spitting and swearing, the actor playing the sex-crazed tyrant spreads his legs, not only to show the power in his muscular appendages, but also to show that he has enormous and powerful “balls” (grennplen), and as he spews out long lists of expressions indicating male genitals, he simultaneously swells out his chest, swivels his hips and moves forward making rhythmic motions imitating sexual thrusting (kouutfoul) as he taunts the artist who is the “un-masculine” figure with the squashed balls, he who is effeminate and fragile and overpowered by other men.

An introduction to Franketienne, I feel, may lead to a lifetime odyssey to understand.

An introduction to Franketienne, I feel, may lead to a lifetime odyssey to understand.

Franketienne’s Brooklyn performance was unlike any I have ever experienced. Singing with a soulful voice, alternating with dramatic narrative interspersed with humorous asides – all in French and Creole – the artist mesmerized the predominantly Haitian-American audience.

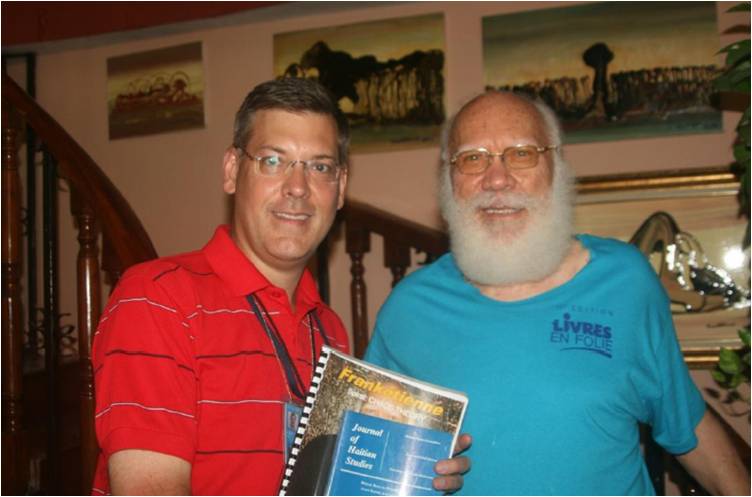

I met Thomas Spear, professor of French at CUNY Graduate Center, at the event. Thomas, I discovered, was a younger colleague of my father’s whose seminal French-language website, Ile en ile, features authors of French-speaking islands, and has chronicled Franketienne for years. Thomas told me:

Not long after meeting you at the Brooklyn Public Library, before Franketienne’s recent performance of Melovivi, I discovered you were the “connecting goodness” man. I was delighted to learn that you are the son of Stanford Luce, whom I had met through our mutual research on the work of Louis-Ferdinand Celine, another writer of explosive and highly inventive language; Franketienne is one of the few, in French language today who gives such life to the language, with energetic explosions of assonant, colorful neologisms.

Thomas told me of listening to septuagenarian Marie Coron reciting with enthusiasm texts of Franketienne she’s learned by heart. Living in Lyons, France, it’s fun to see how Franketienne can connect to others. She, as I, comes from a completely different universe than the writer – yet we are mesmerized. With her declining eyesight, Marie chooses her texts for their value as diction exercises as well as for their performance value.

This CUNY professor also told me about New York-based artist Beatrice Coron, her daughter, appreciates both the visual and textual creativity of Franketienne who, like she, makes much use of wordplay. Beatrice said, when first seeing Galaxie Chaos-Babel, “thank God I’m not Franketienne” (!). Beatrice’s flower books include Fleurs d’insomnie, with petals containing verses of Franketienne.

Emmelie Prophete, whose Le reste du temps will be published by Memoire d’encrier this month, says in French, “Each of Franketienne’s words builds a world of which every Haitian dreams.”

I also met at the event Alessandra Benedicty, another professor of City College of New York. She told me after his performance:

Once I had decided to work on Franketienne for my thesis, what initially interested me in his work was his use of Vodou as an aesthetic system. What I mean by that is that at least my first association with Vodou was as a religion. In academic disciplines, Vodou is often studied in the fields of anthropology or religious studies. As someone who loves literature, my interest in Vodou grew out of Franketienne’s treatment of it as an aesthetic.

Right now, I am working with the conferences that Andre Breton gave when he spent time in Haiti in 1945-1946. Breton sees affinities between Vodou and Surrealism–and where Franketienne puts an accent on the aesthetics of Vodou, Breton talks about the “secular ideals” of “rapprochement” between peoples; he sees Vodou and Surrealism as forms that give way to “liberty and affirmation of dignity.”It’s been over sixty years since Breton’s visit to Haiti–and Surrealism is no longer the “movement” that it had been in the earlier part of the century, yet that said, in reading Breton’s conferences immediately after seeing Franketienne read and perform in New York, I was reminded of Franketienne’s own words: his emphasis on the role of the youth and the importance of aligning the material reality of modern society with a respect and awareness of the human condition.

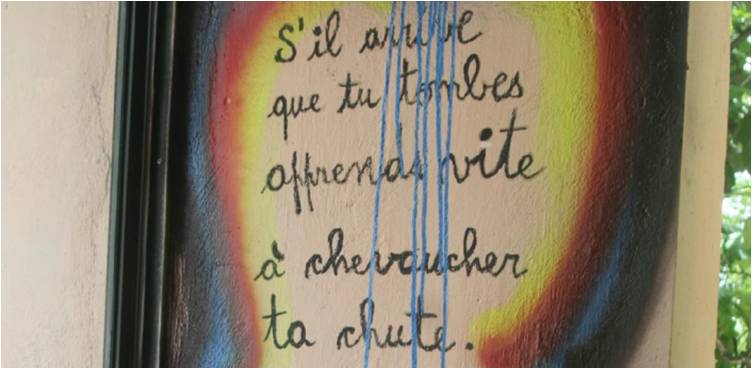

One of the lines that I’ve heard Franketienne repeat over and over, and we even heard a version of it today, is “S’il arrive que tu tombes relève-toi vite, il faut savoir tomber pour apprendre à se relever. Et même s’il advient que tombes souvent, evertue-toi à chevaucher ta chute” — “If it happens that you fall, get back up quickly, you must know how to fall in order to stand back up. And even if you fall often, try your best to sidestep your own fall.”

In the 2005 version of Fleurs d’insomnie–Flowers of Insomnia, Franketienne writes: “Nous escaladons d’audace les risques majeurs, les perils secrets soutenus par les piliers du silence” — “We scale with audacity, the major risks, the secret perils sustained by pillars of silence […].”

It is Franketienne’s audacity in his writing – his charming ability to calmly bring his interlocutor into his initially terrifying world, it is an audacity to imbue the material, whether it be his poetry, his painting or his theatre, with a sense of the urgency of humanity – which makes him such an incredible writer and persona.

Dr. Rachel Douglas of the French Section, School of Cultures, Languages & Area Studies, University of Liverpool told me shortly thereafter:

Melovivi or The Trap is a play which was written almost two months before the earthquake struck Haiti. It’s an almost spookily premonitory play, and it ties in with what has always been a crucial strand of Franketienne’s writing: his focus on natural disaster in Haiti. Environmental disaster has been a constant theme of his work which highlights the ever-worsening environmental situation.

In this play, as in all of Franketienne’s work, the landscape/the environment are represented as a dystopian, desecrated, and nightmarish apocalypse. Natural forces, such as hurricanes, landslides, and floods are always depicted as ferociously attacking the Haitian people, as wreaking destruction on Haiti.This widespread degradation is made particularly prominent in this play by the plethora of strings of words which all mean the same thing. Cumulatively, this pleonasm builds up an impression of complete and utter destruction, for example, different words for ‘rubbish’ are accumulated. Everything is described here as being awash with mud, filth, and excrement, and so repetition of similar words make the piles of rubbish grow even higher.

There are no specific references in this play to a particular natural disaster — it could refer to any of them. It’s also appropriate that the speakers remain anonymous (designated only here as “Speaker A” and “Speaker B”) because they represent the nameless and faceless who die every year when Haiti is hit harder than other Caribbean islands by natural disasters.

I was enormously appreciative of Thomas, Alessandra and Rachel as I had missed much of what Franketienne had said in French and Creole. I will continue to write about Franketienne, and his best-known works in The Stewardship Report (JLSR). I will explore the genre he has perfected known as Chaos Theory. I will also ask Franketienne specialists such as Mary Cobb Wittrock of the University of Maryland, Seanna Sumalee Oakley of the University of Nebraska, and Kaiama L. Glover of Columbia University to share their thoughts on his works.

I have been remiss not to mention that Franketienne’s home is amazing. Three stories tall, the earthquake of January 12, 2010 knocked down most of his walls. With a child-like joie de vivre, Franketienne redecorated his home by painting all the remaining supports. He believes the home is much improved without all the walls. I must concur it was striking.

Franketienne is one of Haiti’s best known intellectuals and artists. He is continuously at the vanguard of artistic thought throughout the Caribbean. He is a creative and political thought leader as well as a global citizen. On The Luce Index™ he ranks 97 out of 100, along with Anwar Sadat, Ban Ki-Moon, Elie Wiesel, and Wynton Marsalis. I encourage the Nobel Prize Committee to bestow upon this great Haitian the first Nobel Prize awarded to any Haitian.

Photos by Jim Luce and Evens Anozine for The Stewardship Report.

The Luce Index™ – Individuals

97 – Franketienne

The Island to Island Website (Ile en ile) of the City University of New York

For sound recordings and archival video on Franketienne + 101 other Haitian writers

Journal of Haitian Studies, University of California SB Center for Black Studies Research

For a number of pieces of Franketienne translated into English

Give me a break!

Did he write this himself??

I know this guy and he is really an egocentric with many Haitians equal or better than him.

But he is a master of self-promotion.