The still ongoing cholera epidemic in Haiti, the first to hit the country in more than 100 years, began in 2010, shortly after a vast earthquake devastated the country killing tens of thousands and leaving infrastructure in ruins.

The still ongoing cholera epidemic in Haiti, the first to hit the country in more than 100 years, began in 2010, shortly after a vast earthquake devastated the country killing tens of thousands and leaving infrastructure in ruins.

It is widely believed that the disease was brought to the country by a team of infected Nepalese peacekeepers stationed in the country, though the UN has asserted that a “confluence of factors” is to blame for the outbreak.

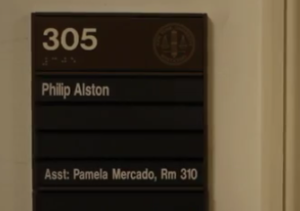

“They’ve been hiding behind that for ages now, but all the evidence shows incontrovertibly that that’s nonsense,” Alston told FRANCE 24.

“The only factor is that these peacekeepers from Nepal arrived with cholera and the excrement was dumped in the river.”

$400 million support package but no apology

Alston’s outspoken comments come as the UN hashes out details of a $400m (366m euros) package to aid victims of the cholera outbreak.

Dr David Nabarro, the British physician appointed by UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon to lead the organisation’s response to the cholera epidemic, said the package would fund a two-track approach.

Half the money would go towards treatment and measures to stop the spread of cholera, Dr Nabarro told FRANCE 24, and the other towards what he called a “support package” – essentially compensation for victims and their families.

The UN will still likely need to depend on voluntary contributions from its members to raise the funds.

“With anything that the UN does we can develop good plans, but we need to raise the money to implement those good plans because we don’t have the cash reserves here,” said Dr Nabarro.

But despite the relief efforts and the fact Ban has admitted the UN has a “moral” obligation to help Haiti’s cholera victims, the organisation has stopped short of formally apologising or admitting legal accountability.

It has also invoked its right to immunity from lawsuits in order to prevent victims suing for compensation. A US federal appeals court upheld the United Nations’ right to immunity in August.

“If the United Nations bluntly refuses to hold itself accountable for human rights violations, it makes a mockery of its efforts to hold governments and others to account,” Alston said in the report.

US pressure

Alston believes that misguided legal advice is the reason for the UN’s reticence.

In his report, Alston accused the UN’s Office of Legal Affairs (OLA) for coming up with a “patently artificial and wholly unfounded legal pretence for insisting that the organisation must not take legal responsibility for what it has done”.

This is “despite the fact that [the UN’s] absolute legal immunity has recently been upheld by courts in the United States of America”, meaning that it has nothing to fear from litigation, according to Alston.

The approach “of simply abdicating responsibility is morally unconscionable, legally indefensible and politically self-defeating,” he wrote in the report.

Alston suggested that the US, the largest financial contributor to the UN, could be placing pressure on the organisation to take such a position.

“In the US, one never accepts legal responsibility, one always accepts a deal or a settlement but never responsibility, and I think that the US wants to follow exactly the same approach in the context of the UN, but the situation is in fact completely different.”

Funding problems?

Alston, though, is pleased with the $400m financial package being put together by the UN, describing it as a “fantastic development”.

“That we have mobilised, in principal, $400m is astounding and I am delighted. But I still insist that it must be done with a legal base – not as charity, but as a matter of legal responsibility on the part of the UN.”

However, whether the UN will be successful in raising the funds still remains unclear.

Dr Nabarro said that discussions with member states had been “promising” when it came to financing the sanitation and disease control part of the relief package, but “less promising” when it came to compensating victims’ families.

“If you deny responsibility then it’s much harder to raise money, to mobilise resources because it becomes just another general development problem,” noted Alston. “And I think the UN has actually exacerbated the problem significantly through its denials for many years.”