So-called boleteros have long been a part of the political firmament in largely Hispanic enclaves in Miami-Dade. But they are part of a burgeoning cottage industry in the Haitian community.

So-called boleteros have long been a part of the political firmament in largely Hispanic enclaves in Miami-Dade. But they are part of a burgeoning cottage industry in the Haitian community.

By Nadege Green

ngreen@miamiherald.com

At Little Haiti’s St. Mary Towers, ballot brokers jockey every election season to see who can get in the doors and collect the most absentee ballots, the elderly residents say.

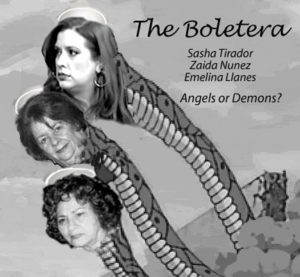

Brokers tout their skills on Creole-language radio, pitch their services to candidates running for office in cities that boast a sizeable Haitian electorate and even brag about their vote-getting prowess on business cards emblazoned with slogans like “Queen of the absentee ballots.”

So-called boleteros have long been a part of the political firmament in largely Hispanic enclaves in Miami-Dade.

But they are part of a burgeoning cottage industry in the Haitian community — a testament to the increasing power of the Haitian-American vote, as well as a cause for concern for those who worry about potential abuses, especially in the wake of the recent arrests of two ballot brokers in Hialeah.

“In areas where people have less sophistication about the process, the idea of someone helping is more appealing,” said Joseph Centorino, director of Miami-Dade’s Ethics Commission. “This kind of thing tends to happen where there are vulnerable people, people who can be taken advantage of by a political campaign.”

The Miami-Dade County State Attorney’s Office has set up a task force to investigate all allegations of possible vote fraud.

At least one senior citizen at St. Mary Towers, a beige corner apartment complex for the elderly, says he is unsure whom he voted for in last month’s election after he let brokers fill out his absentee ballot.

Joseph Jean-Baptiste said three men filled out and mailed his absentee ballot. The men who knocked on his apartment door in Little Haiti spoke Creole. They said they were Democrats and seemed friendly. But Jean-Baptiste can’t say whom he voted for with certainty because he didn’t review the ballot for the Aug. 14 primary except to sign it.

“The government needs to look into this because I had faith in these people and now I don’t know. I keep thinking about it. Did they steal my vote?” said Jean-Baptiste, 84.

Several St. Mary Towers residents told a reporter there were brokers collecting ballots in August.

A Miami-Dade county ordinance prohibits a person from possessing multiple absentee ballots. The ordinance allows people to turn in two absentee ballots in addition to their own.

Alix Desulme, a Haitian-American politician who ran against state Rep. Daphne Campbell in District 108, said he has never been approached by an absentee ballot broker. Desulme lost to Campbell in the Aug. 14 primary.

“I’ve heard there were people who offer to render absentee services in the Haitian community, but I always wanted to run my campaign with integrity and honesty,” Desulme said.

One woman, Noucelie Josna, who calls herself the “The queen of absenstee ballots” on her business card, did work for Desulme when he ran for North Miami city clerk. Desulme said Josna did not collect ballots on his behalf and added he was unaware of her self-proclaimed title when he hired “the queen”.

“She did voter outreach and managed the flier distributions, that was it, nothing out of the ordinary,” he said.

Last month, Hialeah ballot brokers Deisy Cabrera and Sergio Robaina were charged with voter fraud and with violating the county ordinance. The scandal cast the ballot-broker issue into high relief — and had politicians scrambling to distance themselves from boleteros, which has become something of political pejorative this election season.

In the Haitian community ballot brokers are often part of a loose network of voting-booth translators and radio hosts that at least in theory are meant to help guide newly minted voters through the electoral process — one that can be doubly perplexing given the unfamiliarity of the language and a frequent distrust of government.

“Back in Haiti, when voting is being carried out, there’s no guarantee that every vote will count because the process has always been tainted,” said Jocelyn McCalla, a New York-based political analyst and former director of the National Coalition for Haitian Rights. “There is a notion when you vote in the U.S. your vote will count because the process is not tainted.”

McCalla notes that the frequent practice of filling out a ballot with the assistance of a third party, or relying on the so-called translators who escort voters to polling booths to help them with their selections — even though Miami-Dade ballots are printed in Creole as well as Spanish and English — can be problematic.

“When a middle man comes in between, your vote can be diverted,’’ McCalla said.

During election season, dollars from political campaigns fuel an onslaught of advertisements and interviews on Haitian radio, billboards in Creole pop up in Little Haiti, and candidates, many of whom don’t speak Creole, sit in the front pews of Haitian churches for some much-desired face time with potential voters.

On Haitian radio, hosts and paid advertisements during elections tell listeners to call translators or helpers to assist them with their absentee ballots or on voting day. Observers say that although ballots are printed in Creole, some Haitian voters are not necessarily literate in their native language and rely on trusted figures in Haitian media and the community to inform them about candidates.

It is not illegal for voters to receive help filling out their absentee ballots so long as the person who is assisting does not override the voter’s choices or fraudulently sign the ballot for a voter.

“The problem is getting neutral information to the community by parties who are not compromised. That is a pity in the Haitian community because the people rely on Haitian radio and the people who dominate the airwaves have a far more significant impact on the Haitian community than say, an email or other communications,” said McCalla.

While ballot brokering in predominantly Haitian neighborhoods is relatively new — there is not yet a Creole word equivalent to the Spanish boletero — the practice is growing in prominence with each election season.

Volney Nerette, who hosts Ecoutez La Voix Du Peuples — Listen to the Voice of the People — a Creole-language voter-education program on Radio Mega 1700 AM, asks listeners to call on him if they need help to request an absentee ballot or to fill one out.

Nerette is also a paid political consultant. He said there is no conflict .

“When someone calls me, I don’t tell them I’m there from a campaign. That person called me for help,” he said.

Last year, he earned $7,000 as a political consultant in the North Miami Beach mayoral and council election races. Nerette says his duties were mostly to advise candidates.

“During elections, candidates pay people to go on Haitian radio to help people because they are looking for ballots to collect. I’m a professional; I don’t touch the ballots,” he said.

He does, however, solicit political candidates to hire him, touting his access to voters with absentees.

In an email to North Miami mayoral candidate Carol Keys last year, Nerette wrote: “I’m an experience [sic] political specialist consultant I already have 4,500 abst-T [sic] requests between North Miami and North Miami Beach.”

Nerette confirmed he sent the email.

“Oh yeah, at that time I might have made 4,500 requests for people. Right now I might have more than 6,000 to 11,000 requests I made for people, but that doesn’t mean I get the vote. The people I do the requests for they do call me and ask me who my candidates are, but I don’t do it for the candidates. The people ask me. They know me.”

Keys, who lost the election to Mayor Andre Pierre, did not hire Nerette.

“He told me I had to give him money for the absentee vote. I just ignored him and he eventually sent me this email,” Keys said.

At St. Mary Towers, Jean-Baptiste said he never requested an absentee ballot, but one appeared in his mailbox before the Aug. 14 primary.

The self-sufficient octogenarian goes to doctor appointments alone and typically handles his affairs without assistance. Jean-Baptiste said when the three men knocked on his door, he allowed them into his small one-bedroom apartment because he recognized one of them, who had previously visited the complex with state Rep. Campbell.

Jean-Baptiste said he told the three men he wanted to vote for County Commissioner Audrey Edmonson, County Mayor Carlos Gimenez and U.S. Rep. Frederica Wilson, but never checked the ballot afterwards.

“Now I want to see the ballot. When they left I was in doubt,” he said. “I want my absentee ballot back.”

Campbell did not respond to calls or an email for comment

The three men also took Fernande Claude’s absentee ballot. She said the men are doing a public service for the elderly.

“They filled out the form for me and they had me sign it. After they made me sign it , they put their own stamp on it and took it with them,” Claude,78, said.

Mercie Auguste, 87, said she gave her absentee ballot to a woman.

“I let them fill the ballot for me because I don’t know who to choose. They vote for who they wanted,” she said. “When they finish, I sign my name, I give it back to them and I guess they did whatever they wanted with it.”

Hernsie Milfort, assistant manager of St. Mary Towers, said she has fielded complaints from tenants about ballot brokers.

One day in August, three residents came to her office to complain there was a woman in the building asking to collect absentee ballots, she said.

Absentee ballot assistance and visits by political campaigns are arranged by Samuel Roker, the onsite social-service coordinator, Milfort said.

Roker denied scheduling ballot assistance by outsiders, but said he does allow candidates to meet with residents before every election. He also helps residents who come to him to fill out absentee ballots.

“I addressed this problem with the tenants,” Roker said. “When we have presentations in the community room we tell them not to give people their absentee ballots.”

Milfort, the assistant manager, said she did not alert police or ask the woman to leave despite the complaints.

“Certain things I don’t have control of. I don’t want to be in trouble,’’ she said. “It’s not my job to control that.”