By Jacqueline Charles

It’s time for the United Nations’ 2,300 blue-helmet soldiers in Haiti to head home after 13 years, the head of the world body recommended in a report to the U.N. Security Council this week.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said that the peacekeeping operation in Haiti should close by Oct. 15. Guterres made the recommendation in a 37-page U.N. report obtained by the Miami Herald.

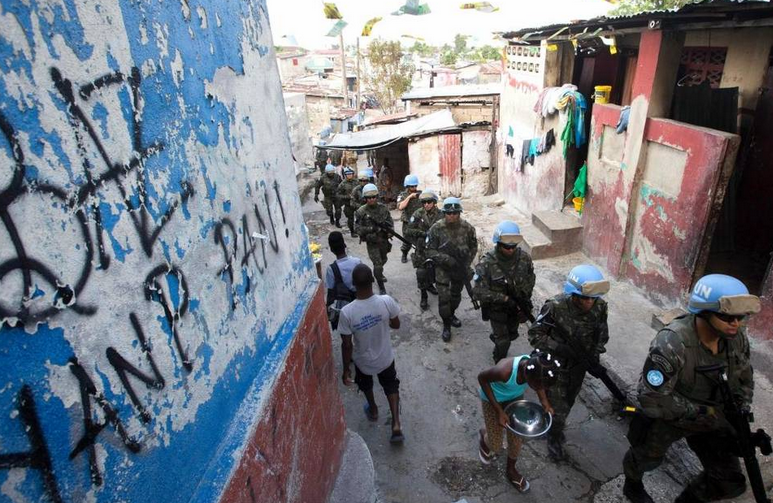

“The military component should undergo a staggered but complete withdrawal of the 2,370 personnel,” Guterres said of the U.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti, which is more commonly known by its French acronym, MINUSTAH.

Guterres’ recommendation comes as President Donald Trump seeks to significantly cut the United States’ U.N. contribution with a particular focus on reductions in peacekeeping, environment and development. At the same time, the Trump administration is proposing to slash funding for the U.S. Agency for International Development, Haiti’s biggest donor.

As part of the phasing out of MINUSTAH after more than a decade in Haiti, Guterres is recommending that the $346 million mission “be extended for a final period of six months” after its current mandate expires on April 15. The U.N. Security Council is expected to debate Guterres’ recommendations — including the future role of the United Nations in Haiti — on April 11.

While Security Council members all agree on the draw-down, there is disagreement on the future of the U.N.’s presence in Haiti. Guterres is recommending that a smaller mission replace MINUSTAH to focus on police development and the country’s dysfunctional judiciary.

The move had been expected since last month, when U.N. Undersecretary General for Peacekeeping Operations Hervé Ladsous visited Haiti and told the Miami Herald that “the military component is not necessary anymore.”

Guterres agrees.

But the last time the U.N. attempted to transition out of Haiti, an armed revolt forced the deployment of more than 6,000 troops. This time, Guterres said, the proposed withdrawal should be “gradual” in order to give the Haiti National Police time to take responsibility for the country’s security.

“Such a strategy would reduce the possibility of a repetition of the failures of past transitions, such as the rapid decline of HNP capacity, impartiality and credibility following the closing of the U.N. peacekeeping operation in Haiti in March 2000 which led to the ensuing electoral crisis and large-scale public unrest,” Guterres said in the report.

Guterres said the new mission also would be mandated to help strengthen human rights in Haiti. It would still maintain a political section, while the number of civilian employees would be reduced by 50 percent. Meanwhile, the U.N. foreign police presence also would be reduced, deployed only to five regions to provide back-up to Haiti National Police.

Overall, the number of foreign police officers in Haiti would be reduced from 1,001 to 295. They would be charged with mentoring and offering strategic advice to senior-level Haiti National Police officers.

Foreign diplomats acknowledge that the Haiti police force has made great strides — it was key in the recent arrest of alleged drug trafficking fugitive Guy Philippe — but Guterres said it “has yet to build adequate capacity to address all instability threats inside the country, independently of an international uniformed presence and in line with human rights standards.”

Haiti’s “longstanding risks of instability caused by a combination of a culture of zero-sum politics, deep-rooted political polarization and mistrust, poor socio-economic and humanitarian conditions as well as weak rule of law institutions and serious human rights challenges,” suggests the need for continued support for the national police, Guterres said, especially in gang-ridden metropolitan Port-au-Prince, and in the southern and northern region where police presence remains low.

“Haiti is still in a delicate period of political transition, pending the formation of the new government and the definition of its governance priorities,” he said.

On Thursday, Haiti’s Senate approved the policy statement of recently designated Prime Minister Jack Lafontant. Lafontant, who lacks political experience and has made sweeping promises to turn around the country’s fortunes, still must get the approval of the Lower Chamber of Deputies. He and his cabinet are expected to go before the body on Monday.

The new government’s lack of political experience is not the only challenge facing Haiti, which has seen a steep decline in foreign aid dollars since its devastating Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake, and the suspension of some budgetary support from donors after a fraud-marred 2015 presidential election led to an interim government.

Guterres noted that the U.N. has struggled to raise money for humanitarian assistance for Haiti after it was slammed by Hurricane Matthew in October, and to address the cholera epidemic. A March 6 letter sent to U.N. member states asking how much they intended to contribute to a $400 million Haiti cholera eradication plan has received lukewarm responses.

“As the United Nations gradually and responsibly draws down its presence, I encourage international partners and individual member states to also review the support they provide to Haiti to minimize the risk of jeopardizing the gains so far achieved,” Guterres said.