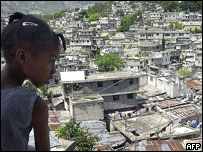

Nearly $1 billion in investments in Haiti’s northern corridor is creating fears that the jobs will lead to the creation of slums.

Nearly $1 billion in investments in Haiti’s northern corridor is creating fears that the jobs will lead to the creation of slums.

By Jacqueline Charles

jcharles@MiamiHerald.com

CARACOL, Haiti — Braving the heat, Fanilia Prospère took a break from pushing her wheelbarrow of imported used clothing to look around. Then she smiled.

In Haiti, where so many promises of change turn to dust, the evolving landscape was worth the moment of contemplation: warehouse-sized factory shells rising from fertile soil, bulldozers rumbling distantly as they cleared farmland to build hundreds of homes and unemployed young men chattering under a mango tree about the change that was coming to Caracol.

“Caracol is getting another image,” said Prospère, 30, a mother of three. “There are a lot of people who weren’t working, but they are now working. And a lot of people who want to work and who I believe will be soon working.”

For the bucolic but impoverished fishing village on Haiti’s northern coast, the sight of foreign dollars creating new housing and jobs is filled with hope — and worry that the multi-million dollar investments also will spawn the all-too-familiar slums.

“It is almost certain,” said Jilson St. Tilien, as he watched a game of dominoes under the tree. “People need to make a living and they will move here to do so.”

Desperate for any good news after the devastating January 2010 earthquake, the Haitian government signed off on the 600-acre industrial park in this remote rural village without preparing for how the region should eventually look — or absorb the promised jobs. Only now is a zoning plan being developed, but residents and Haiti watchers wonder if it’s coming too late.

Their anxiety is fueled by Haiti’s historically weak institutions and the rush by the international community and Haiti’s leaders to show progress. It is also a reflection of the challenges of working in Haiti where there is continuous friction between need-to-spend foreign aid agencies, which are often perceived as arrogant, and a weak central government.

As a result, Haiti analysts say, projects are often haphazardly started with too little preliminary planning, lopsided consultation and inadequate environmental impact studies.

“The international community has been under immense pressure to show movement and this is the closest they’ve come to have something significantly positive to say about Haiti, investments and jobs,” said Carlo Dade, a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa’s School of International Development and Global Studies. “But on the other hand, this is really one case where there is no excuse for not getting it done right.”

From the start, U.S. and Haitian officials have heaped billboards of praise on the $300 million investment. But it quickly became a target of criticism.

While supporters tout the park and its amenities as a steel and concrete example of rebuilding Haiti after the quake, agriculturalists and environmentalists criticized its location on prime arable land at the mouth of an already endangered marine and mangrove-forest ecosystem.

Others worry that while the park’s job-creation benefits may help to depopulate Haiti’s teeming capital city 82 miles away, it risks replicating the very social and political ills that have plagued sprawling slums like Cité Soleil.

“When you look at the social problems that Cité Soleil poses today, you have to ask, did it have to be that way?” said Michèle Oriol, executive secretary of Haiti’s Inter-ministerial Commission on Territorial Planning, which has objected to the park’s location, and that of a U.S.-financed housing development just off the main commercial corridor.

“The North-Northeast region is today enjoying a concentration of investments. That is a big deal in Haiti,” she said. “But there is a price to be paid. There are a series of measures that need to be taken.”

The U.S. government and Inter-American Development Bank, which are jointly funding the industrial park’s development, say while it is the most visible symbol of post-quake progress, it is only part of the investment that donors are pouring into the northern corridor to spur economic growth. About $1 billion is being invested in agriculture, electricity, health, housing, roads and schools.

“We heard the government after the earthquake when they said, ‘We want to create other regions where people have reasons to stay, and livelihoods that they can pursue.’ Our investments in the north were designed to meet that goal,” said Cheryl Mills, counselor and chief of staff for U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who has held town hall meetings in Haiti about the park. “This is really for us an opportunity to bring the one thing that people have said most intensively that they need and want. They want jobs.”

Scholar Alex Dupuy, who has written extensively about the failures of Haiti’s cut-and-sew economy, says while the current push to revive Haiti’s garment assembly industry may come with what he calls “side benefits” — roads, port upgrades and a new $45 million power plant, to name a few — the strategy “has absolutely nothing to do with creating a sustainable growth economy in Haiti.”

“It’s about tapping a source of cheap labor,” said Dupuy, a Haiti-born sociology professor at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. “They did the same thing in Port-au-Prince, which had people leaving the countryside because of the free-trade policies that have devastated the Haitian agriculture sector. So the fear that the region will be flooded is very real.”

Late last year, President Michel Martelly, who inherited the project from the previous administration, agreed to ask the American Institute of Architects to work with the eight local communities affected by the planned development to create a regional master plan.

The plan takes into account not just the park and its 65,000 projected jobs but 5,000 proposed USAID and IDB-financed homes for the corridor; a recently built private high school; and yet-to-open Dominican Republic-financed university in the nearby town of Limonade. Also part of the mix is the potential impact of U.S.-financed regional hospitals’ upgrades, construction of roads and a new seaport in nearby Fort Liberté. A planned Venezuela-financed upgrade to the Cap-Haitien airport is also being considered.

Erica Gees, executive director of AIA’s nonprofit arm, said up to 35 planners and designers have been working on the regional plan, which will need to be adopted by all affected communities. Among the recommendations that will be presented in late June, Gees said, will be infrastructure upgrades in existing communities to absorb the growth. The park is expected to attract up to 300,000 new residents, or five people for every one worker hired. With town populations currently ranging between 1,500 and 25,000 residents, Gees said, residents’ fears are real and legitimate.

“You have a very solid existing social structure. People know each other; they have been farming the same land for generations. There is a real sense of security,” she said. “You want to enhance that by integrating newcomers into each town in a more organic process. By combining urban upgrades and expansion with strategic placement of services and public space, you can ease the impact of rapid growth.”

Oriol’s agency had made similar recommendations in order to help reduce possible conflict with residents and prevent the main commercial corridor from being blocked should unrest occur. Her group was asked by former Prime Minister Garry Conille to intervene after regional parliamentarians, complaining they had been left out of the loop amid meetings between U.S. officials and local mayors, objected to the location and size of the U.S.-planned houses near the main access road.

Conille put the housing on a permanent hold, but Martelly, who didn’t want to delay the housing construction, overruled him.

The U.S. has since modified the housing scheme, increasing the sizes of the houses slightly and pushed the development further off of the street to allow for future expansion of the road. But lawmakers like Pierrogene Davilmar remain unhappy.

“We know the country,” he said, adding that the current location will still wreak havoc and the overall project has been too piecemeal. “These things require a minimum amount of planning.”

One thing that has been well-planned is the engineering of the actual industrial park on former farmland.

Last month, as the first four hurricane and seismic-resistant buildings were completed, hundreds of Haitians were inside laying electricity cables, unpacking boxes and assembling chairs and work stations. All four buildings belong to Korean garment manufacturer Sae-A, a major supplier of U.S. retailers. As the park’s anchor tenant, Sae-A will create 20,000 jobs over four years, and occupy 23 custom buildings, including 12 factories of 120,000 square feet each. Value of Sae-A’s Haiti investment: $74 million.

Among the park’s highlights: the best drainage system in Haiti with man-made lagoons to control flooding; landscaping and paved roads; a police station, clinic, customs office and power station with fossil fuel and solar power; a 46-room wired executive hotel with another one being planned; and a $14 million water treatment facility. Sae-A plans to open Haiti’s first textile fabric mill, which has raised concerns among environmentalists. They point out that an IDB consultant’s report noted there wasn’t enough time to evaluate the potential impact of the garment dyeing on the nearby ecosystem. U.S. officials say the park will meet international standards, and the treated water will be cleaner than the soiled water currently flowing into a nearby river.

“No matter the drawbacks, Caracol, however you look at it, is more than a positive step,” said businessman Rudolph Boulos, a former senator for the northeast region. “The fact that the people have less and less to do — no agriculture, no work. Even with the sea next door, Caracol has become a brothel of the North and Northeast.”

Still, residents have mixed feelings about the coming transformation of this historical region, which gave birth to the country.

“When you aren’t working, you have no other choice but to take what you can,” said Estefan Paul, taking a break from his $5-a-day manual labor job inside one of the new factories.

“The local authorities, they don’t speak up for you. Whatever the foreigners say they are going to do, they accept.”

Haiti Commerce Minister Wilson Laleau said he understands the concerns. But Haiti, he said, has to start somewhere to create jobs.

“The industrial park is not a solution that will resolve all of the problems,” he said. “But it is one of the mechanisms that will help us to find a solution to have money circulated in the region, and that will allow for other activities like tourism and agriculture to develop so that we can develop a middle class. A lot of countries have taken this route.’’