Graham Greene is a literary legend, famous for best-selling spy novels like Our Man in Havana, The End of the Affair, and The Quiet American. But the writer was as mysterious as his characters: secretive and prone to bouts of bipolarism. Few people really ever got to know him.

Surprisingly, one of the men who knew him best now lives in a modest Miami apartment. But Bernard Diederich has one helluva story to tell in his own right.

The veteran Haiti correspondent tells New Times how he survived Central America’s civil wars, Papa Doc’s torture cells, and drinking whiskey with the greatest spy novelist to have ever lived.

Diederich sits at a desk in his Coral Gables home and remembers an era of spies, civil wars, and political assassinations.

The bookshelves behind the New Zealand-born newsman are full of the books he’s written – mostly on dictators like Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Anastasio Somoza, and Rafael Trujillo – as well as relics of his own amazing life, including a replica of the four-masted sailboat he sailed on as a 16-year-old during World War II. But the one thing that predominates — both on the shelves and in conversation — is Greene.

“He was a real loner,” Diederich, now 86, says of the writer. “But we became very good friends.”

That unto itself would be quite an accomplishment, given Greene’s lifelong struggle with bipolar disorder. But Diederich and Greene’s relationship went much deeper. For several decades, the two traveled throughout Haiti and Central America together. Those adventures — full of whiskey and political intrigue — were the fodder of Diederich’s reporting and Greene’s novels.

One trip, in particular, is legendary, largely because Greene used it as the basis for his 1966 novel The Comedians. Diederich had moved to Port-au-Prince in 1949 and founded a newspaper. After Papa Doc came to power in 1957, journalism became much more dangerous. In the spring of 1963, the dictator known as le Zombificateur — “the Zombie maker” — for the way he scared his subjects into submission, began “disappearing” his political opponents.

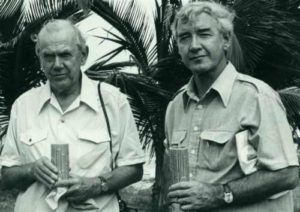

|

| Courtesy of Bernard Diederich |

| Graham Greene during a trip to Haiti |

Diederich reported as dozens of military officers were rounded up. But when he himself was arrested and thrown in the National Penitentiary, Diederich found it oddly quiet. It wasn’t until his release that he realized the officers had been killed.

“They were specialists in breaking bones,” Diederich says of Papa Doc’s thugs, known as tonton macoutes. “Their brand of torture was to hang you up and break the bones off of you.”

Diederich was released unharmed and managed to escape the country, followed by his wife and young child. They relocated to the Dominican Republic, where Greene soon paid them a visit. He, too, had been to Haiti to witness the atrocities underway.

“He was really shaken by what he had seen,” Diederich remembers. Over Barbancourt rum, the two men became friends. And in 1965, when Greene visited again, Diederich took him on a three-day trip along the border.

Accompanied by a Haitian priest whose family had been “disappeared” by Duvalier, the two writers visited the former insane asylum that had become a Haitian rebel camp. The bizarre scene went straight into Greene’s novel.

“The building was terrible. It was full of goat shit, piled high,” remembers Diederich. “The rebels were using World War I Enfield rifles bought from a Cuban in Miami.”

Duvalier banned both the book and movie versions of The Comedians from Haiti. But Greene kept writing, and Diederich kept on helping him. The reporter introduced the novelist to Latin American heavyweights like Panamanian president Omar Torrijos, Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and even Fidel Castro.

Over the years, the two developed an almost father-son relationship. The enigmatic Greene opened up in hundreds of letters, written in tiny penmanship he had developed as a spy. Diederich would visit him in his tiny apartment in Antibes, France, and always find him at his desk, pen in one hand, a midday martini in the other.

Diederich is now also opening up. He has written a book about the friendship titled Seeds of Fiction: Graham Greene’s Adventures in Haiti and Central America 1954-1983.

“I felt like so many people had written such trash about him, some of it completely fabricated,” he says. “When I first met him, I thought he was your typical stuffy Englishman.”

So much for that idea.