BY TRENTON DANIEL

BY TRENTON DANIEL

tdaniel@MiamiHerald.com

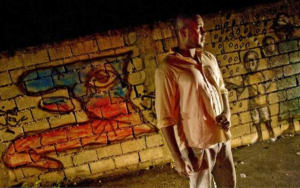

PETIONVILLE, Haiti — On a soggy Friday night, the graffiti artist known as “Jerry” scooped up a half-dozen aerosol cans from the back of his Toyota RAV4, placed them at the base of a cinder block wall in this Port-au-Prince suburb and proceeded to spray.

Four minutes later, the work was finished — a map of quake-cracked Haiti with a weeping eye in the center — and then a bonus: a quake victim with her two children, a tearful son in tattered shorts pleading with an upturned palm in a rainstorm.

The work was signed “Jerry.”

“They can only hope that help is coming soon,” Jerry Rosembert Moise — better known as “Jerry” — said as he studied the pieces. “With the rainy season, we won’t know how long they’ll be suffering.”

Moise, 25, feels compelled to articulate the frustrations of the 1.5 million displaced people still living in open-air camps almost six months after Haiti’s Jan. 12 quake claimed an estimated 300,000 lives. His trademark map of a cracked Haiti — visible on so many crumbly walls in Port-au-Prince — reflects the country’s cries for help.

City walls have long served as forums for Haiti’s messy politics. Political parties employ freelancers to creep through the night to disparage opponents on building facades.

These days, graffiti presses for the departure of President René Préval and the many nongovernmental organizations from abroad. In the past few weeks, graffiti has called for the return of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, the playboy head of state who was ousted in 1986 and now lives in France.

But Moise is not a hired gun.

AN OPEN SECRET

A graphic artist by training, he resembles a lesser-known Banksy, the anonymous British  street artist whose satirical works have surfaced in places from post-Katrina New Orleans to the Palestinian territories.

street artist whose satirical works have surfaced in places from post-Katrina New Orleans to the Palestinian territories.

Like Banksy, Moise sneaks around at night, spraying vertical spaces with what some deem to be works of art; the walls are his canvas, the Port-au-Prince metropolis a museum. But unlike Banksy, Moise is much better known — in Haiti, at least — in that there’s little mystery about his identity.

His work comes at a time when Haitian street artists are shirking conventions. Whereas paintings used to be confined to the galleries in the hills above the capital, slum-based artists have plucked scraps of junk from the streets to build sculptures and, just last fall, organized an arts festival in downtown Port-au-Prince.

To one local artist, Moise’s work mixes Haiti’s long-standing traditions of street art, as demonstrated on the tap taps — brightly painted buses — and cunning political satire, seen in the cartoons in newspapers and online.

`SOMETHING NEW’

“Jerry came with something new, with something we weren’t used to. Walls were used for advertising or political propaganda,” said Philippe Dodard, a well-known Haitian artist whose own works take on a graphic color-fused motif and not what some would consider traditional art.

“Jerry does it out of his own freedom and out of his own thoughts. And if you look at the messages of Jerry, you could say they are a kind of art.”

Moise’s motivations are spurred by creative forces, not by politics.

Moise has painted more than 50 pieces, ranging from social commentary to portraits of weeping people to the ubiquitous map of a quake-cracked Haiti.

His work reveals a world in which politicians are animals or inanimate objects. They are suit-clad, sunglass-sporting dogs or, more recently, hammers that nail down the nation and thwart progress.

Other pieces to pop up in the past few weeks: a flag-waving, soccer ball-holding man watching the World Cup on a TV set propped up by cinder blocks and a stocking-clad, cigarette-smoking woman peering suggestively over her shoulder as if onlookers — almost certainly foreigners — were supposed to chat her up or more.

Other pieces to pop up in the past few weeks: a flag-waving, soccer ball-holding man watching the World Cup on a TV set propped up by cinder blocks and a stocking-clad, cigarette-smoking woman peering suggestively over her shoulder as if onlookers — almost certainly foreigners — were supposed to chat her up or more.

“I definitely believe this is something we need to take seriously because it’s an expression of young Haitians,” said Maryse Kedar, coordinator for the group Progress and Development Through the Youth of Haiti. “The messages are extremely powerful.”

With the help of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Kedar’s group commissioned Moise to paint more than 80 large tanks of drinking water. The tanks — and Moise’s handiwork — can be seen in camps from Petionville’s Place Boyer to downtown Port-au-Prince.

Moise does tributes, too. Shortly after Michael Jackson died last year, he sprayed his own rendition, sunglasses, pointy chin and all. It made international headlines.

In some paintings, Moise makes use of the natural environment. Hovering shrubs are hair and errant pipes are poles. In many of the portraits, the subjects look out onto the streets and cry. And even as he mixes up the subject matter, he sticks to a signature tag, rendering the piece unmistakably his.

AS SEEN ON YOUTUBE

Moise’s speed and dexterity are evident on YouTube.

The clips shows a masked and hooded Moise as he steps on a concert stage in downtown Port-au-Prince’s Champ de Mars plaza and proceeds to wield a pair of spray-paint cans. In just three minutes, a depiction of Rick Ross, the Miami rapper, comes to fruition — bulky sunglasses, bushy beard, shiny dome. The whole thing is done from memory.

“Bon bagay, bon bagay,” a commentator says over and over. Good thing, good thing.

The idea of using spray-paint cans and to create socially conscious images on walls initially came from Moise’s mentor, Papa Katafalk, the leader of a Creole hip hop group called Barikad Crew. Tragically, the band lost three members in a car crash in 2008. Another died in the quake.

“Katafalk said, `Maybe you should do graffiti as a way to change the country,’ ” Moise recounted. “I said, `Yeah, I had something like that on my mind.’ ”

As he navigated the traffic-heavy streets of his native Port-au-Prince and eyed the walls on a recent Sunday, Moise noted how he wants his work to go beyond the pedestrian graffiti that has long been the norm: political propaganda.

It seems as though there isn’t a wall left in the capital that isn’t defaced with “aba,” Creole for “down with,” or “vote” for one candidate or the other — the obvious handiwork of freelancers seeking to advance the respective agendas of their office-seeking employers.

“Spre isn’t for aba or vote,” said Moise, reiterating a message that appears on several of his pieces. For Moise, an art-school drop out, spre means access to a platform on which he can articulate Haiti’s myriad frustrations and problems.

“My mission is to spre for everybody,” he said. “So that somebody can come get us out of this mess.”

I am in Petionville and his artwork is all over the place.

Some of it has a Disney flavour